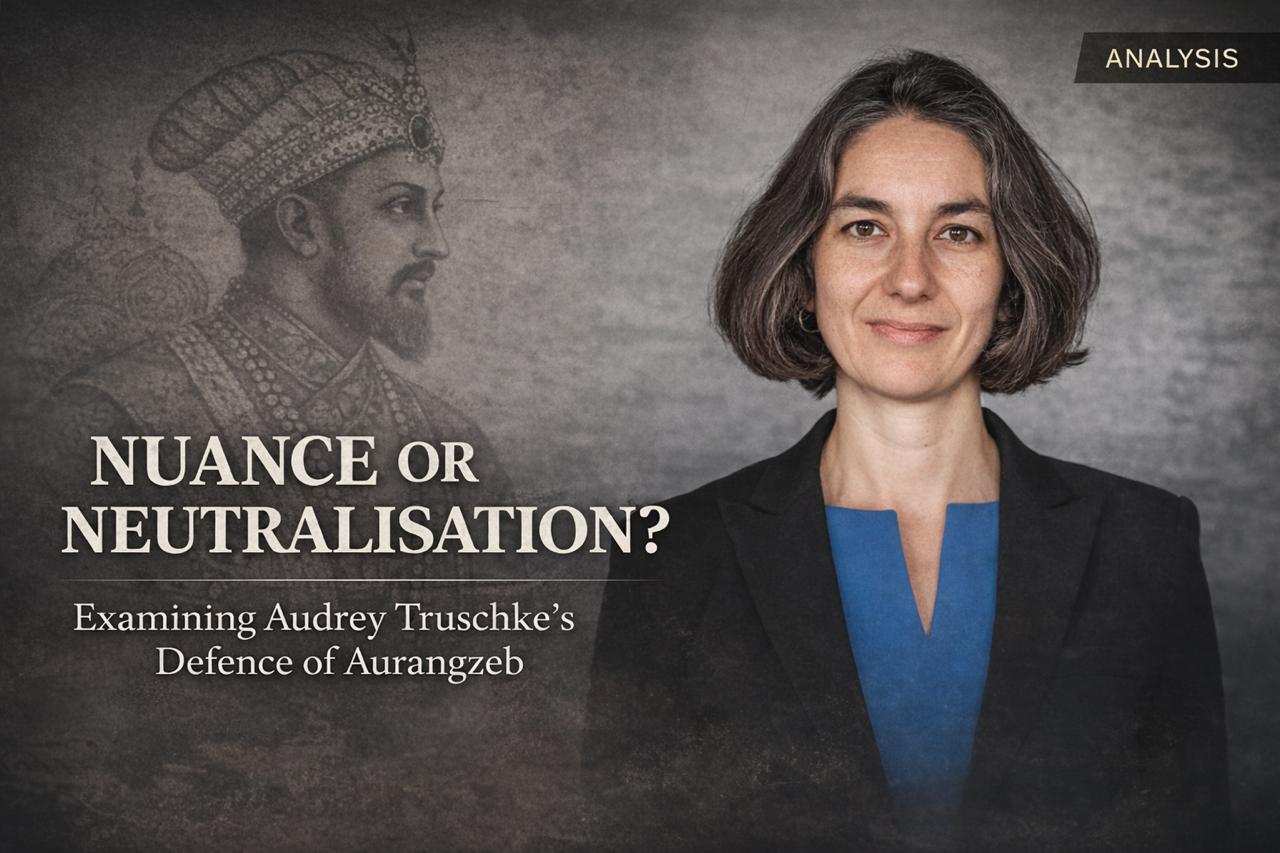

Expansion, temples and jizya: Putting Audrey Truschke’s Aurangzeb argument to a historical stress test

Today, Audrey Truschke is among the most controversial foreign academics commenting on Indian history, having acquired widespread notoriety in a relatively short span. She is one of the most vocal public defenders of Aurangzeb, repeatedly arguing that his negative portrayal in India is the result of political imagination rather than historical reality. In multiple interviews and public discussions, she challenges the popular characterisation of Aurangzeb as a religious tyrant and instead presents him as a pragmatist whose actions must be understood within the norms of pre-modern empire-building. Recently, she went to Pakistan and gave an interview to Aeon, a Pakistani Podcaster. This article examines her claims through her statements and arguments on the podcast. Redefining “success”: When expansion is treated as achievement At the very beginning of her argument, Truschke frames Aurangzeb as the “most successful” Mughal ruler by foregrounding territorial expansion, emphasising that he added nearly a quarter more land to the empire and ruled over a larger population than any other pre-modern Indian monarch. While these claims might seem true, they rest on an impoverished definition of success that treats conquest as a self-justifying achievement. What remains conspicuously unexamined is the cost of this expansion, which includes the decades of continuous warfare, fiscal depletion, administrative overreach, and the systematic erosion of provincial governance. After his death, the Mughal state began unravelling almost immediately. By isolating territorial scale from its consequences, this framing converts imperial overstretch into accomplishment and reduces “success” to mere acreage, while excluding durability, legitimacy, and state capacity from the historical assessment. The ‘not a religious tyrant’ claim: Dilution through context After presenting Aurangzeb as a “successful” ruler, Truschke goes on to argue that he has been wrongly portrayed as a religious tyrant. According to her, his negative image is exaggerated, shaped by British colonial writing, and amplified today by Hindutva politics. While challenging colonial exaggerations is valid, the problem arises in what follows. In pushing back against one extreme, she creates another, where well-documented actions such as temple destruction, the re-imposition of jizya, restrictions on Hindu religious practices, and punitive measures against Shia groups are repeatedly explained away as practical or political decisions rather than part of a broader religious policy. This downplay becomes difficult to sustain when one looks at indigenous Mughal-era sources themselves. Court chronicles such as Maʾāsir-i-ʿĀlamgīrī, written by Saqi Must‘ad Khan during Aurangzeb’s reign, explicitly record the 1669 imperial order directing provincial governors to act against the “schools and places of worship of the infidels,” followed by the destruction of major temples at Banaras and Mathura.Similarly, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab by Khafi Khan is hardly a hostile work or documents the re-imposition of jizya and the suppression of non-Islamic practices as part of imperial policy. Even Mughal court histories authored by Hindu officials, such as ‘Futuhat-i-Alamgiri’, acknowledge temple demolitions and religious regulations, despite being written under imperial patronage. These records predate British colonial rule and cannot be dismissed as colonialinventions. This way of interpreting Aurangzeb’s actions quietly shifts the debate. Instead of examining how Islam played an important and consistent role in his rule, the discussion is shifted to explaining each controversial act one by one as a special situation. When every action is treated as an exception, the overall pattern disappears. The events are not denied, but their importance is steadily reduced. What finally emerges is an image of Aurangzeb as just another power-hungry medieval ruler, rather than a king whose reign clearly marked a turn towards stricter Islamic policy compared to earlier Mughal emperors. At the same time, the argument changes the nature of the debate itself. The focus moves away from Aurangzeb’s policies and towards the motives of those criticising him. Dissenters are portrayed as driven by modern political agendas, while the defence is framed as objective scholarship. Colonial propaganda argument: From correction to overcorrection Audrey Truschke’s justification of Aurangzeb is based in large part on the assertion that his unfavourable reputation is a product of British colonialism. Colonial historians selectively accentuated Mughal brutality to justify imperial control. However, acknowledging colonial distortion does not automatically invalidate the underlying historical record. The problem arises when this corrective effort turns into overcorrection. Truschke’s argument frequently implies that because the British amplified Aurangzeb’s cruelty, the foundational evidence itself m

Today, Audrey Truschke is among the most controversial foreign academics commenting on Indian history, having acquired widespread notoriety in a relatively short span. She is one of the most vocal public defenders of Aurangzeb, repeatedly arguing that his negative portrayal in India is the result of political imagination rather than historical reality. In multiple interviews and public discussions, she challenges the popular characterisation of Aurangzeb as a religious tyrant and instead presents him as a pragmatist whose actions must be understood within the norms of pre-modern empire-building. Recently, she went to Pakistan and gave an interview to Aeon, a Pakistani Podcaster. This article examines her claims through her statements and arguments on the podcast.

Redefining “success”: When expansion is treated as achievement

At the very beginning of her argument, Truschke frames Aurangzeb as the “most successful” Mughal ruler by foregrounding territorial expansion, emphasising that he added nearly a quarter more land to the empire and ruled over a larger population than any other pre-modern Indian monarch. While these claims might seem true, they rest on an impoverished definition of success that treats conquest as a self-justifying achievement. What remains conspicuously unexamined is the cost of this expansion, which includes the decades of continuous warfare, fiscal depletion, administrative overreach, and the systematic erosion of provincial governance. After his death, the Mughal state began unravelling almost immediately. By isolating territorial scale from its consequences, this framing converts imperial overstretch into accomplishment and reduces “success” to mere acreage, while excluding durability, legitimacy, and state capacity from the historical assessment.

The ‘not a religious tyrant’ claim: Dilution through context

After presenting Aurangzeb as a “successful” ruler, Truschke goes on to argue that he has been wrongly portrayed as a religious tyrant. According to her, his negative image is exaggerated, shaped by British colonial writing, and amplified today by Hindutva politics. While challenging colonial exaggerations is valid, the problem arises in what follows. In pushing back against one extreme, she creates another, where well-documented actions such as temple destruction, the re-imposition of jizya, restrictions on Hindu religious practices, and punitive measures against Shia groups are repeatedly explained away as practical or political decisions rather than part of a broader religious policy.

This downplay becomes difficult to sustain when one looks at indigenous Mughal-era sources themselves. Court chronicles such as Maʾāsir-i-ʿĀlamgīrī, written by Saqi Must‘ad Khan during Aurangzeb’s reign, explicitly record the 1669 imperial order directing provincial governors to act against the “schools and places of worship of the infidels,” followed by the destruction of major temples at Banaras and Mathura.Similarly, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab by Khafi Khan is hardly a hostile work or documents the re-imposition of jizya and the suppression of non-Islamic practices as part of imperial policy. Even Mughal court histories authored by Hindu officials, such as ‘Futuhat-i-Alamgiri’, acknowledge temple demolitions and religious regulations, despite being written under imperial patronage. These records predate British colonial rule and cannot be dismissed as colonialinventions.

This way of interpreting Aurangzeb’s actions quietly shifts the debate. Instead of examining how Islam played an important and consistent role in his rule, the discussion is shifted to explaining each controversial act one by one as a special situation. When every action is treated as an exception, the overall pattern disappears. The events are not denied, but their importance is steadily reduced. What finally emerges is an image of Aurangzeb as just another power-hungry medieval ruler, rather than a king whose reign clearly marked a turn towards stricter Islamic policy compared to earlier Mughal emperors.

At the same time, the argument changes the nature of the debate itself. The focus moves away from Aurangzeb’s policies and towards the motives of those criticising him. Dissenters are portrayed as driven by modern political agendas, while the defence is framed as objective scholarship.

Colonial propaganda argument: From correction to overcorrection

Audrey Truschke’s justification of Aurangzeb is based in large part on the assertion that his unfavourable reputation is a product of British colonialism. Colonial historians selectively accentuated Mughal brutality to justify imperial control. However, acknowledging colonial distortion does not automatically invalidate the underlying historical record.

The problem arises when this corrective effort turns into overcorrection. Truschke’s argument frequently implies that because the British amplified Aurangzeb’s cruelty, the foundational evidence itself must be treated with suspicion. This overlooks the fact that long before British historians wrote about Aurangzeb, Mughal-era Persian sources recorded temple destruction, religious decrees, and the re-imposition of jizya as matters of state policy. Texts such as Maʾāsir-i-ʿĀlamgīrī and Muntakhab-ul-Lubab were composed by court historians during or immediately after Aurangzeb’s reign. These were not colonial fabrications but internal records of the Mughal state.

Although they may have influenced tone and focus, colonial writers did not create the events. One distortion is replaced by another when colonial mediation is used as an excuse to completely ignore indigenous facts. Erasing unfavourable primary sources because they contradict a preferred narrative is not the same as historical rectification.

Temple destruction as ‘politics’: Where the explanation breaks

Truschke frequently contends that Aurangzeb’s destruction of temples was situational and political, connected to uprisings or threats to imperial authority rather than religious motivations. Political motivations certainly played a role in several cases, but as a general model, this argument falls apart.

Over several decades, Aurangzeb demolished temples in Banaras, Mathura, Maharashtra, and the Deccan. It is difficult to link many of these incidents to immediate uprisings. More significantly, even throughout protracted military engagements, Aurangzeb has not ordered the destruction of any mosques against competing Muslim powers. One would anticipate comparable acts against Islamic places of worship if temple destruction were only a political tactic. They are noticeably missing.

Furthermore, a number of documented instances transcended devastation and descended into symbolic religious humiliation. According to Persian chronicles, idols taken from temples were positioned beneath the steps of mosques so that worshippers would trample them. Political expediency alone is insufficient justification for such actions. Devastation stops appearing random and begins to resemble policy when it persists over time, is repeated across regions, and is accompanied by overt religious symbolism.

Court praise and ‘Hindu officials’: The problem of court sources

The existence of Hindu officials and court records written by Hindus endorsing Aurangzeb is another recurrent point in Truschke’s defence. She contends that this disproves allegations of religious persecution. This is flawed because the nature of court sources is not understood.

Neither Muslim nor Hindu chroniclers of the Mughal court were impartial observers. They were totally dependent on imperial patronage for their jobs, earnings, and safety. In court histories, praise indicates closeness to authority rather than freedom of speech. Knowing that deviating from imperial expectations could result in either professional or personal destruction, a Hindu official working in the Mughal government wrote under tight restrictions. Therefore, using court praise or Hindu participation in the state as proof of religious tolerance confuses proximity to power with genuine social harmony.

Dara Shikoh vs Aurangzeb: A false comparison that hides real differences

Truschke rejects the common comparison that presents Dara Shikoh as more open or pluralistic and Aurangzeb as rigid or orthodox. She argues that neither was “secular” and that both used religion for political purposes. While it is true that modern ideas of secularism cannot be applied to pre-modern rulers, this does not mean the two were the same in practice.

Dara Shikoh supported the translation of philosophical texts, engaged seriously with non-Islamic traditions, and encouraged intellectual exchange across religious lines. Even though his worldview remained Islamic, his approach to culture and governance was relatively open. Aurangzeb, on the other hand, reduced religious flexibility, prioritised Islamic law in state policy, and rolled back several accommodative practices followed by earlier Mughal emperors.

These distinctions remain even if one accepts that neither ruler satisfies contemporary secular norms. Important differences in how they governed and how religion influenced their policies are flattened when both are treated as merely “political users of religion”.

Conclusion: Nuance cannot become neutralisation

The issue about Aurangzeb isn’t about whether history should be nuanced. The question is whether nuance should be utilised to clarify the record or to gradually dilute it. Audrey Truschke describes herself as addressing colonial misconceptions and present political exaggerations. That remedial impulse is, in principle, valid. However, rectification does not imply selective reductionism.

Territorial growth cannot be considered unquestionably successful while administrative collapse is ignored. Repeated temple demolitions cannot be permanently reframed as independent political activities when they occur across regions and decades. Jizya re-imposition cannot be dismissed as pragmatism because it formalised religious differentiation inside state policy. Court appreciation cannot be confused with civilisational endorsement. And dismissing modern secular designations does not eliminate significant religious disparities among Mughal princes.

The primary sources of his own era record decisions that shaped the Mughal Empire in lasting ways – politically, legally, and religiously. Recognising those realities is a historical responsibility. Nuance is valuable, but when it consistently bends toward reduction, it ceases to illuminate and begins to obscure.