Love jihad dismissed, conversions ignored, Hindu expression labelled hate: How CSOH’s hate speech report distorts data to push an anti-Hindu narrative

On 17th January, Congress MLA from Karnataka, Priyank Kharge, took to social media to amplify a report by the Washington-based Centre for the Study of Organised Hate and claimed that a majority of so-called hate speech incidents in India in 2025 originated from Bharatiya Janata Party-ruled (BJP) states. He further claimed that these incidents largely targeted minorities. A report by the Washington-based research group India Hate Lab found that 88% of documented anti-minority hate speech events in India in 2025 occurred in BJP-ruled states. Of the 1,318 hate speech events recorded, 98% targeted Muslims.308 speeches (23%) contained explicit calls… pic.twitter.com/v4P48q5b5z— Priyank Kharge / ಪ್ರಿಯಾಂಕ್ ಖರ್ಗೆ (@PriyankKharge) January 17, 2026 The post did not merely share the report but presented its conclusions as established facts. He used the report to target the BJP and even singled out Union Home Minister Amit Shah, accusing him of being one of the leading figures driving hate speech. Apart from Kharge, the likes of The Quint, Alt News and The Wire jumped to take advantage of the report. The Quint’s report based on CSOH’s publication revolved around the so-called hate speeches against the Christians and the Muslims.However, the report only talked numbers and did not present any example that was noted as “hate speech” by the India Hate Lab. In 2025, on an average, four hate speech cases were reported every day.2025 was a year which witnessed an increase in hate speech against Muslims and Christians, in newer forms, more intensity and magnitude. As per the new India Hate Lab report by @csohate showed how 1,164 hate… pic.twitter.com/RBfttbnpBd— The Quint (@TheQuint) January 14, 2026 In its report based on CSOH publication, The Wire’s report claimed that 656 hate speeches of all speeches talked about “conspiracy theories” including “love jihad”, “land jihad”, and more. India Saw 1,318 Hate Speech Events in 2025; 98% of Them Targeted Muslims: ReportUttar Pradesh, with 266 instances, recorded the highest number of hate speeches in 2025, followed by Maharashtra, with 193 such cases.Sharmita Karhttps://t.co/HGxa7MRBMX— The Wire (@thewire_in) January 15, 2026 The report titled “Hate Speech Events in India” claimed to document 1,318 in-person incidents across the country in 2025. It projected a sharp rise in such incidents compared to the previous year. It further asserted that expressions linked to Hindu organisations, religious events, political campaigns, and social mobilisation are part of an organised ecosystem of hate. The sweeping claims made by CSOH in its report have since been echoed by sections of the political opposition and activist networks. However, there is little scrutiny of how such incidents have been defined, selected, or interpreted by the Washington-based organisation. A closer reading of the report has raised serious questions about its credibility, intent, and methodology. It has labelled well-documented criminal patterns as “conspiracy theories” and has classified religious commemorations and historical assertions as hate speech. The study appears less like an objective examination of social realities and more like an ideological exercise designed to criminalise one side of India’s political and civilisational discourse. How activism is repackaged as methodology in the so-called hate speech study The core of the CSOH report is a methodology that does not merely analyse so-called hate speech but actively predefines it through a highly biased ideological lens. The study states that it classifies hate speech using a “United Nations framework”. It further claims that it adopts an expansive definition that treats any communication deemed “pejorative” or “discriminatory” towards a group based on identity as “hate speech”. This broad framing immediately blurs the distinction between criminal incitement, political speech, religious expression, historical assertions, and social mobilisation. It allows the report to sweep a wide range of lawful and constitutionally protected activities into its dataset. The report further introduces “dangerous speech” as a subcategory. It has been drawn from the “Dangerous Speech Project” to argue that certain narratives increase the risk of audiences participating in violence. However, instead of demonstrating how specific speeches led to actual violence or imminent harm, the methodology assumes causality by treating narrative expression itself as evidence of intent. Such an approach replaces legal thresholds with speculative interpretations. In such cases, perceived ideological motivation becomes sufficient to label speech as dangerous without any evidence of violence whatsoever. In its methodology, CSOH argues that expressions of anger by sections of the Hindu community are not organic reactions but the result of strategic planning by “entrepreneurial merchants of hate”. This style of framing leaves no room for ackn

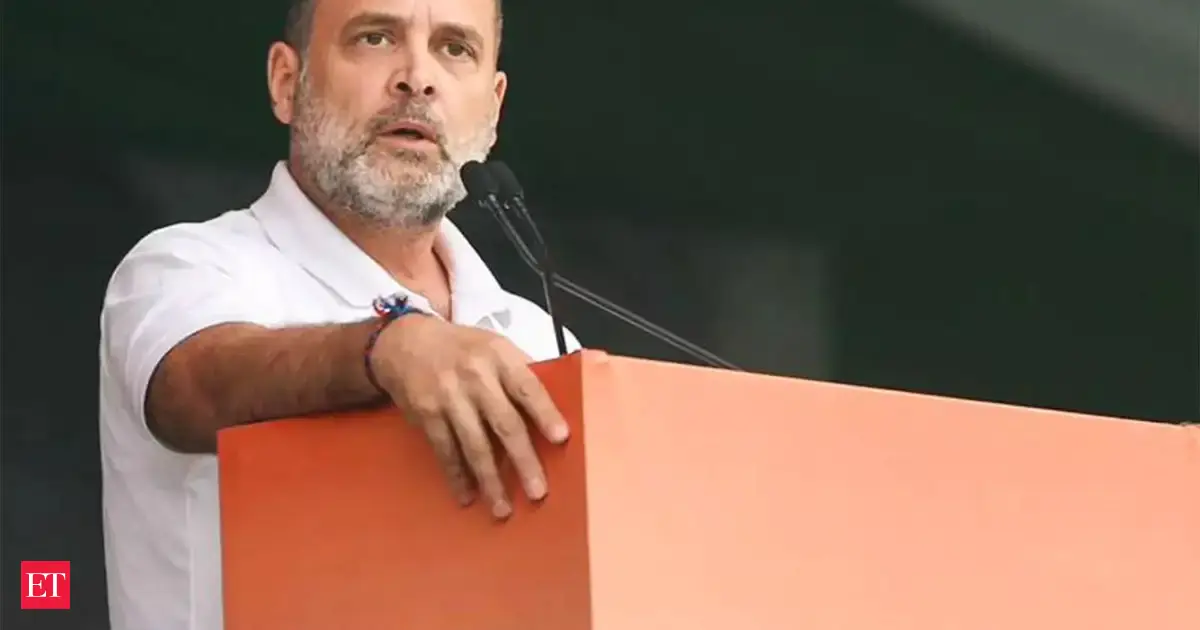

On 17th January, Congress MLA from Karnataka, Priyank Kharge, took to social media to amplify a report by the Washington-based Centre for the Study of Organised Hate and claimed that a majority of so-called hate speech incidents in India in 2025 originated from Bharatiya Janata Party-ruled (BJP) states. He further claimed that these incidents largely targeted minorities.

A report by the Washington-based research group India Hate Lab found that 88% of documented anti-minority hate speech events in India in 2025 occurred in BJP-ruled states. Of the 1,318 hate speech events recorded, 98% targeted Muslims.

— Priyank Kharge / ಪ್ರಿಯಾಂಕ್ ಖರ್ಗೆ (@PriyankKharge) January 17, 2026

308 speeches (23%) contained explicit calls… pic.twitter.com/v4P48q5b5z

The post did not merely share the report but presented its conclusions as established facts. He used the report to target the BJP and even singled out Union Home Minister Amit Shah, accusing him of being one of the leading figures driving hate speech.

Apart from Kharge, the likes of The Quint, Alt News and The Wire jumped to take advantage of the report. The Quint’s report based on CSOH’s publication revolved around the so-called hate speeches against the Christians and the Muslims.However, the report only talked numbers and did not present any example that was noted as “hate speech” by the India Hate Lab.

In 2025, on an average, four hate speech cases were reported every day.

— The Quint (@TheQuint) January 14, 2026

2025 was a year which witnessed an increase in hate speech against Muslims and Christians, in newer forms, more intensity and magnitude. As per the new India Hate Lab report by @csohate showed how 1,164 hate… pic.twitter.com/RBfttbnpBd

In its report based on CSOH publication, The Wire’s report claimed that 656 hate speeches of all speeches talked about “conspiracy theories” including “love jihad”, “land jihad”, and more.

India Saw 1,318 Hate Speech Events in 2025; 98% of Them Targeted Muslims: Report

— The Wire (@thewire_in) January 15, 2026

Uttar Pradesh, with 266 instances, recorded the highest number of hate speeches in 2025, followed by Maharashtra, with 193 such cases.

Sharmita Karhttps://t.co/HGxa7MRBMX

The report titled “Hate Speech Events in India” claimed to document 1,318 in-person incidents across the country in 2025. It projected a sharp rise in such incidents compared to the previous year. It further asserted that expressions linked to Hindu organisations, religious events, political campaigns, and social mobilisation are part of an organised ecosystem of hate.

The sweeping claims made by CSOH in its report have since been echoed by sections of the political opposition and activist networks. However, there is little scrutiny of how such incidents have been defined, selected, or interpreted by the Washington-based organisation.

A closer reading of the report has raised serious questions about its credibility, intent, and methodology. It has labelled well-documented criminal patterns as “conspiracy theories” and has classified religious commemorations and historical assertions as hate speech. The study appears less like an objective examination of social realities and more like an ideological exercise designed to criminalise one side of India’s political and civilisational discourse.

How activism is repackaged as methodology in the so-called hate speech study

The core of the CSOH report is a methodology that does not merely analyse so-called hate speech but actively predefines it through a highly biased ideological lens. The study states that it classifies hate speech using a “United Nations framework”. It further claims that it adopts an expansive definition that treats any communication deemed “pejorative” or “discriminatory” towards a group based on identity as “hate speech”.

This broad framing immediately blurs the distinction between criminal incitement, political speech, religious expression, historical assertions, and social mobilisation. It allows the report to sweep a wide range of lawful and constitutionally protected activities into its dataset.

The report further introduces “dangerous speech” as a subcategory. It has been drawn from the “Dangerous Speech Project” to argue that certain narratives increase the risk of audiences participating in violence. However, instead of demonstrating how specific speeches led to actual violence or imminent harm, the methodology assumes causality by treating narrative expression itself as evidence of intent.

Such an approach replaces legal thresholds with speculative interpretations. In such cases, perceived ideological motivation becomes sufficient to label speech as dangerous without any evidence of violence whatsoever.

In its methodology, CSOH argues that expressions of anger by sections of the Hindu community are not organic reactions but the result of strategic planning by “entrepreneurial merchants of hate”. This style of framing leaves no room for acknowledging legitimate grievances, documented crimes, or demographic and social anxieties. By design, the methodology treats outrage as manufactured and victimhood narratives as tools of manipulation. Interestingly, this treatment is present only when articulated by one side.

The bias becomes more evident when the report lists types of “hate speeches”, which include the propagation of so-called “jihad-based conspiracy theories”, calls for economic or social boycotts, demands related to places of worship, and references to issues such as Bangladeshi or Rohingya infiltration.

The report does not examine whether such claims are rooted in documented cases, court proceedings, police records, or government data. Rather, it categorically labels them as conspiratorial and hateful at the outset.

This pre-judgement is most evident in the section dealing with “jihad” narratives. Terms such as love jihad, land jihad, vote jihad, population jihad, education jihad, economic jihad, halal jihad, and others are uniformly described as baseless conspiracy theories. The methodology makes this declaration without engaging with criminal complaints, FIRs, ongoing investigations, or judicial observations related to forced religious conversions, targeted exploitation, or demographic manipulation.

The report claims to apply the Rabat Plan of Action’s six-part threshold test, covering context, speaker, intent, content, extent, and likelihood of harm. However, there is little evidence of this test being applied in a transparent or verifiable manner. There is no disclosure of how intent was conclusively determined, how likelihood and imminence of violence were assessed, or how speeches were differentiated from political rhetoric or religious mobilisation. Instead, intent and harm appear to be inferred from the identity of the speaker and the nature of the theme, rather than from demonstrable outcomes.

Furthermore, the data collection process is also problematic. It openly states that it monitors and tracks Hindu right-wing groups and affiliated political actors. It relies heavily on social media scraping, activist networks, and selected media reports. The methodology does not indicate comparable tracking of Islamist groups, radical clerics, or organisations linked to violence against Hindus. The asymmetry in the process of creating the report ensures that one category of actors is permanently under surveillance while others remain largely outside the scope of analysis.

The report also relies on a network of activists and journalists to collate and report incidents, a process it presents as comprehensive and verifiable. Yet, it does not explain how ideological alignment within these networks is accounted for, how confirmation bias is mitigated, or how selective reporting is avoided. The admission that the dataset is not exhaustive and that many incidents lack verifiable content further undermines claims of methodological rigour.

What the methodology conveniently ignores is the scale and nature of crimes directed at Hindus. Data compiled by Hinduphobia Tracker records a total of 4,619 hate crimes against Hindus, including 261 reported deaths since its inception. In 2025 alone, 2,486 cases were documented, comprising over 300 cases of love jihad, more than 600 instances of hate speech targeting Hindus, over 750 cases of predatory proselytisation or forced religious conversion, and numerous other offences. These figures highlight how entire categories of crime are dismissed as conspiracies by CSOH, while responses to them are reframed as hate speech.

CSOH declared certain crimes fictitious and treated resistance or mobilisation against them as hateful by definition. Its report transformed activism into methodology, and the result is not an objective study of hate speech in India but a curated narrative where data is filtered through ideological assumptions. Realities that are inconvenient for the other side are excluded, and lawful expressions are criminalised to fit a predetermined conclusion.

Declaring ‘love jihad’ a conspiracy while ignoring documented cases on the ground

One of the most flawed datasets in the CSOH report is its blanket dismissal of love jihad. CSOH has called it a “baseless conspiracy theory”. The methodology does not merely question the term or seek evidence; it categorically declares the phenomenon fictitious. CSOH did not engage with police complaints, FIRs, court proceedings, or media reported cases that contradict this assertion.

To put things in perspective, data compiled by Hinduphobia Tracker clearly shows that in 2025 alone, there were over 300 cases of ‘crimes against women in relationships and other sexual crimes’, which largely include cases of ‘love jihad’. The total number of such documented cases has crossed 900 since the platform’s inception. These cases include allegations backed by victim testimonies, police action, and ongoing investigations, none of which find acknowledgment in the CSOH study.

Love jihad refers to a pattern of cases in which Hindu women are deceived, coerced, or manipulated into relationships or marriage by Muslim men who present themselves as Hindus by using false names or concealing their religious identity.

These cases are often followed by pressure or inducement to convert to Islam and may involve emotional exploitation, threats, isolation from family, or inducements linked to marriage. Such cases are treated as criminal matters when evidence of coercion, fraud, or forced conversion emerges, and each instance is examined on the basis of individual facts, victim testimony, police investigation, and judicial scrutiny.

There is no blanket rule to treat all relationships between Hindu women and Muslim men as ‘love jihad’. It is only called ‘love jihad’ when the Muslim man has concealed his identity and presented himself as a Hindu to lure a Hindu woman into a relationship. These cases have exploded in several states across the country, leading to strong opposition by Hindu groups including the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and Bajrang Dal.

CSOH has declared love jihad a conspiracy theory at the methodological level. Its report precludes any empirical examination of these cases. As a result, responses to documented crimes are reframed as hate speech, while the crimes themselves are erased from the narrative.

This selective blindness shows how the study has substituted ideological positions for ground realities and reduced complex criminal patterns into dismissible labels rather than subjects of serious inquiry.

For instance, in December 2025 alone, Hinduphobia Tracker documented 14 such cases, each pointing to a pattern of identity concealment, sexual exploitation, and coercive pressure for religious conversion. These incidents, recorded through police complaints and ongoing investigations, stand in sharp contrast to the CSOH report’s dismissal of love jihad as a conspiracy. Here is the brief of 10 of the 14 cases documented in December 2025.

In Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, a Hindu woman was deceived by a Muslim man, Juhur, who posed as a Hindu. On 31st December 2025, he lured her to a secluded forest area on the pretext of a New Year meeting and raped her. The victim approached the police the same night, following which a case was registered and the accused was arrested.

In Bijnor, Uttar Pradesh, a Hindu minor girl was targeted on social media by a Muslim man, Sameer alias Waseem, who posed as a Hindu named Aman. He used a fake profile to gain her trust and later blackmailed her using private chats and images to pressure her for sexual relations. The accused was caught and handed over to the police, following which legal action was initiated.

In Fatehpur, Uttar Pradesh, a Dalit Hindu woman alleged prolonged sexual exploitation and blackmail by a railway employee who posed as a Hindu named Vishal but was later identified as a Muslim, Adnan. He drugged and raped her, recorded obscene videos, and used them to blackmail her over several years while pressuring her to convert and marry him. Police registered an FIR and arrested the accused, with investigations ongoing.

In Patna, Bihar, a Hindu girl was deceived and sexually exploited by a Muslim man, Mohammad Rustam, who posed as a Hindu named Sonu after contacting her through a wrong number call. He sexually exploited her under the false promise of marriage and later recorded an obscene video. When the victim discovered his real identity and refused to continue the relationship, he uploaded the video online, following which the police arrested him based on her complaint.

In Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand, Hindu women were lured and befriended on social media by two Muslim men who posed as Hindus using fake identities. The accused, who ran a salon in the area, were confronted by members of Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Sena on 17th December 2025 and handed over to the police. Authorities stated that the matter was under investigation at the time of reporting.

In Ratlam, Madhya Pradesh, several Hindu girls studying at a government college in Sailana were lured and targeted by a Muslim youth, Kamran Khan, who posed as a Hindu using multiple fake Instagram profiles. He also wore a kalava to reinforce his false Hindu identity while interacting with the girls. Following a complaint by Bajrang Dal and Vishwa Hindu Parishad on 15th December 2025, the police seized his mobile phone for cyber examination and produced him before the court, sending him to jail as the investigation continued.

In Khandwa, Madhya Pradesh, a Dalit Hindu woman was deceived, raped, and blackmailed by Muslim man, Salman, posed as a Hindu named Sanjay for religious conversion. He used obscenely edited photographs to extort money and sexually exploit her over several years, and also sexually assaulted her minor daughter. Police registered a case under rape, blackmail, religious conversion, and SC ST Act provisions and arrested the accused.

In Mandawar, Bijnor, Uttar Pradesh, a Hindu girl was deceived and sexually exploited by a Muslim man, Faizan Malik, who posed as a Hindu named Saurabh Pal using a fake Instagram profile. After she discovered his real identity and withdrew, he blackmailed her with personal photos and pressured her to convert and marry him. Police registered a case for identity fraud, sexual exploitation, and intimidation, arrested the accused, and sent him to jail.

In Noida, Uttar Pradesh, multiple Hindu women were targeted by a Muslim man, Harun Khan, who posed as a Hindu to deceive and sexually exploit them. He is accused of blackmailing victims using obscene videos and pressuring them to convert to Islam, while also threatening those who approached the police. Police registered a case at Bisrakh police station and stated that the accused has multiple prior cases involving similar offences.

In Khandwa district, Madhya Pradesh, a Hindu woman was lured into a relationship by a married Muslim man, Meherban Munir, who initially concealed his identity and later pressured her to convert to Islam. He recorded objectionable videos without her consent, blackmailed and assaulted her, and, along with his wife, circulated the videos after she refused conversion and married someone else. Police registered a case under rape, assault, blackmail, religious conversion, and IT Act provisions and took the accused into custody.

Shaurya Diwas, Babri demolition remembrance, and the distortion of historical disputes

The CSOH report repeatedly categorised Shaurya Diwas, the annual remembrance of the demolition of the disputed structure, the Babri mosque, on 6th December 1992, as hate speech. Expressions of pride or public remembrance related to the event have been grouped with calls for violence, effectively portraying them as organised hatred.

In doing so, the report flattened a long-standing historical and legal dispute into a moral accusation. It ignored the fact that the Babri structure was a disputed site, a reality acknowledged in court proceedings for decades and which resulted in the site being handed over to Hindus. After 500 years of struggle, Hindus got the land back, that too legally, and built the Bhavya Ram Mandir at the site.

For Hindus, Shaurya Diwas is not a celebration of violence against any community. It is a symbolic assertion of civilisational self-respect. The pride associated with the demolition flows from how the event is interpreted by those who commemorate it, not from how ideological critics choose to frame it.

Historical symbols have always carried different meanings for different groups. Just as some revere monuments like the Taj Mahal as a ‘symbol of love’ despite contested histories, Hindus view the demolition of the Babri structure as the removal of a symbol of historical subjugation.

By branding such remembrance as hate speech, the CSOH report effectively criminalised historical interpretation and selective memory. It denied Hindus the same space routinely granted to others to articulate their understanding of the past. This absence of historical nuance revealed how the report’s conclusions were driven less by legal or scholarly standards and more by ideological discomfort with Hindu assertion.

How the CSOH report targets Hindus opposing Christian missionary conversions

The CSOH report repeatedly framed opposition to Christian missionary activity as hate speech. Interestingly, it did so without distinguishing between lawful protests, documented grievances, and criminal incitement. Hindu groups opposing forced or inducement-based conversions have been portrayed as perpetrators of anti-Christian hatred. CSOH did not consider police complaints, FIRs, or ongoing investigations into conversion practices and moved ahead with labelling opposition to such activities as hate speech.

In several instances, public protests, awareness campaigns, and statements warning against predatory proselytisation have been categorised as hate speech, while the circumstances that triggered these responses were ignored. The report does not examine whether conversions were voluntary or under legal scrutiny. Instead, resistance itself is treated as evidence of hostility towards Christians.

The methodology further dismissed concerns about missionary inducements by labelling terms such as “conversion mafia” or references to demographic manipulation as conspiracy theories. This approach allowed the report to invert roles, presenting missionaries as victims and local Hindu communities as aggressors, regardless of the factual background.

Notably, the CSOH study applies no comparable scrutiny to missionary activity, including questions around foreign funding, inducements, or compliance with state anti-conversion laws. By excluding these elements, the report reduced complex local disputes into one dimensional narrative, where Hindus opposing conversion activities have been criminalised through the language of hate speech, while the underlying allegations prompting such opposition were erased from the analysis.

In December alone, OpIndia reported at least five cases linked to alleged forced or inducement-based Christian conversions across different states. These incidents, involving police complaints, local protests, and ongoing investigations, underline why resistance to missionary activity cannot be dismissed as hate speech without examining the facts on the ground.

Police in Fatehpur arrested pastor David Gladwin and his son on 28th December over allegations of luring poor Hindus to convert through inducements and intimidation. An FIR was registered under BNS provisions and the Uttar Pradesh anti-conversion law following a complaint by a local resident. The complainant alleged objectionable remarks against Hindu deities, pressure to convert, and promises of money, jobs, and education during church gatherings. He further stated that villagers were offered cash to stay silent and threatened if they refused to participate or bring others to prayer meetings. Following protests by Hindu organisations, police intervened, detained the pastor, and began recording statements to determine whether coercion or inducement was involved.

A sessions court in Nadiad rejected bail pleas of Steven Bhanubhai Mekwan and Smitul Philipbhai Mahida in an illegal religious conversion case on 20th December. The court found a prima facie case under the Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act and the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita. Police alleged inducement-based conversions targeting tribal communities and minors, including baptisms without parental consent. Investigators cited foreign funding, digital evidence of repeated programmes, and absconding accused with foreign links. The court held that granting bail could endanger witnesses and hamper the investigation.

Police in Sri Ganganagar, Rajasthan, detained six persons, including a German couple, on 18th December for illegal religious conversion activities. An unauthorised church was found operating inside a rented house, where people were lured with money, faith healing promises, and abusive remarks against Hindu deities. Foreign nationals were found present without required permissions in a sensitive border area. Police recovered evidence of organised conversion attempts under the guise of curing ailments.

Police in Chhattisgarh’s Korba district booked Pastor Bajrang Jaiswal after a prayer meeting allegedly used to push religious conversion. The event targeted poor, sick and vulnerable villagers by claiming miraculous healing through prayers. Locals objected and the village sarpanch filed a formal complaint. Police intervened amid rising tensions and registered a case.

Police in Sonbhadra, Uttar Pradesh, arrested Pastor Ramu Prajapati after he and his wife were accused of attempting to convert Hindus by offering money. The couple organised healing and deliverance meetings to lure locals into Christianity. BJP Yuva Morcha and Bajrang Dal members protested after learning about the activity. Police seized religious materials and electronic devices from the spot. An investigation confirmed the allegations, leading to the pastor’s arrest while his wife was absconding.

Who is behind the report, Raqib Hameed Naik and the Hindutva Watch ecosystem

CSOH is founded and headed by Raqib Hameed Naik, who serves as its Executive Director. Naik is also the founder of Hindutva Watch, a platform that claims to track human rights abuses in India in real time, and India Hate Lab, which claims to document and categorise so-called hate speech incidents targeting religious minorities, online and offline. The report published by CSOH is based on the “findings” of India Hate Lab or IHL. Notably, when Vivek Agnihotri’s film The Kashmir Files was released, Naik not only played victim card but also denied Hindu genocide that led to exodus of Kashmiri Hindus from the vally.

In addition to these roles, Naik is reportedly associated as a fellow with Bard College’s Human Rights Project and the Political Conflict, Gender and People’s Rights Initiative at the University of California, Berkeley. He has been cited by media outlets including The New York Times, Al Jazeera, CNN, BBC, the Washington Post and others. This visibility has allowed his claims and datasets to travel widely in global discourse on India. Interestingly, his claims often travel without rigorous scrutiny of their underlying assumptions or ideological positioning.

Hindutva Watch, founded and operated by Naik from the United States, has attracted sustained criticism for its lopsided and selective portrayal of events in India. The account gained notoriety for repeatedly distorting facts, presenting ideological disagreement as hate speech, and consistently maligning Hindu leaders who openly assert their religious identity. Figures such as T Raja Singh, Kajal Hindustani, and others who have spoken on Hindu issues have frequently been targeted by the platform through clipped videos, decontextualised statements, and loaded descriptions.

In January 2024, the Hindutva Watch account on X was withheld in India. This action followed a report by Disinfo Lab, which flagged troubling links between the platform and Pakistan based political propaganda networks. According to the report, Hindutva Watch had used a map embedded by Sardar Adil Kayani, an individual associated with propaganda operations linked to Pakistan’s ruling party, the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz. These revelations further raised questions about the ecosystem within which the platform operates and the interests it serves.

The account was also known for employing vague and elastic terms such as “extreme hate speech” without clearly defining what constituted hatred, often equating factual reporting, religious expression, or political speech with incitement. Despite this ambiguity, Hindutva Watch was routinely amplified by a familiar set of activists, including self-styled fact checkers and members of the leftwing ecosystem, who have consistently projected India in a negative light, particularly since Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power in 2014.

Conclusion

The CSOH report, amplified by political actors like Priyank Kharge and media houses like The Quint, Alt News and The Wire, presents activism as analysis and ideology as evidence. The selective definition of hate speech given in the report, while ignoring documented crimes and criminalising Hindu responses to real grievances, has effectively distorted India’s social realities. Lawful speech, historical memory, and resistance to coercion were reframed as hatred. The actual victims were erased while writing the biased and one-sided report. This is not neutral research, but narrative building, where conclusions are decided first and data is arranged later.