‘Savarna marriages and movements are inherently narcissistic and anti democratic’: Meet the Ambedkarite dean at Galgotias casting an entire community as flawed

Galgotias University recently faced scrutiny after a robotic dog was showcased in a manner that suggested it was developed at the university. Subsequent reports stated that the device was a China manufactured product. The university later clarified that it had not claimed to have developed the robot and described the backlash as propaganda against it. However, there is enough evidence that Professor Neha Singh of the university categorically claimed that the robodog was built at the university. While Professor Neha and others from the university claimed they never said the robodog was made on campus, the matter escalated to a level that, according to sources, they were asked to step away from participation in the government organised AI Impact Summit 2026. As the university came under scrutiny, its professors and deans from other departments are also facing examination. One such professor linked to the university is Professor Ravikant Kisana. Though he is currently serving as Dean of the School of Liberal Education and Languages at the university, the controversy around Galgotias has triggered a wider examination of the intellectual climate within the institution and the ideological positions of its faculty. The dean who wrote ‘Meet the Savarnas’ Prof Ravikant Kisana publicly identifies as an Ambedkarite and OBC intellectual. He authored the 2025 book ‘Meet the Savarnas: Indian Millennials Whose Mediocrity Broke Everything’ and wrote a series of articles examining what he termed “Savarna culture”. Source: X In the prologue of his book, he described elite savarnas as people “who critique everyone and everything but never themselves.” This was not presented as a critique of certain individuals or institutional behaviours. It was framed as a defining trait of a broad caste category. Two lines from the book became especially controversial on social media are “Savarna marriages are inherently narcissistic” and “Savarna movements are inherently anti-democratic.” Savarna marriages are inherently narcissistic. Savarna movements are inherently anti-democratic.#Galgotias University's Dean, School of Liberal Education in his book "Meet The Savarnas" pic.twitter.com/opTAir0p1w— Gems of Indian Academia (@GemsofAcademia) February 18, 2026 The use of the word “inherently” was striking. It suggested that narcissism and anti-democratic tendencies were intrinsic to marriages and movements of a particular caste group, not contingent on context, ideology or circumstance. Such framing moved beyond structural critique into essentialist characterisation. When social analysis attributes moral or psychological qualities to an entire community, it risks replicating the very logic of collective judgement it claims to oppose. From privilege analysis to civilisational indictment The subtitle of the book itself declared that Savarna millennials’ “mediocrity broke everything.” In later chapters, Kisana wrote that Savarnas “inherited institutions and shrank them.” He portrayed Savarna dominance as responsible for stagnation in politics, academia, corporate life and civil society. He repeatedly used the metaphor of a “glass floor” to argue that Savarnas remained structurally insulated even when they experienced anxiety. While examining structural privilege is a legitimate exercise, his language often implied that Savarna insecurity was exaggerated theatre rather than genuine experience. The critique did not remain confined to institutional power structures. It extended into psychological terrain. Savarnas were portrayed as incapable of self-reflection, morally insulated and structurally resistant to democracy. Structural inequality deserves serious scrutiny. But when an argument assigns inherent moral deficiency to a broad category of people, it invites the same kind of collective stereotyping that modern constitutional frameworks seek to transcend. ‘Shaadi like a Savarna’ and cultural disdain In his article “Shaadi Like a Savarna”, Kisana examined elite weddings and described them as “the ultimate barometer for a deeply conservative and exclusionary Savarna social order.” He wrote that such weddings were performances of “power, pride and vanity” and suggested that even self-described progressive Savarna youth ultimately reverted to Brahmanical conservatism at the altar. He contrasted these weddings with Satyashodhak marriages and framed Savarna cultural practices as hollow spectacle masking regressive caste mandates. Critiquing caste endogamy and ritual hierarchy has been happening for a long time. However, describing the wedding culture of millions as intrinsically narcissistic and exclusionary did not distinguish between variation, reformist strands or changing social patterns. It treated an entire community’s cultural practices as fundamentally suspect. Selective moral indictment of majority cultural expressions, while presenting others as inherently emancipatory, risks subs

Galgotias University recently faced scrutiny after a robotic dog was showcased in a manner that suggested it was developed at the university. Subsequent reports stated that the device was a China manufactured product. The university later clarified that it had not claimed to have developed the robot and described the backlash as propaganda against it.

However, there is enough evidence that Professor Neha Singh of the university categorically claimed that the robodog was built at the university. While Professor Neha and others from the university claimed they never said the robodog was made on campus, the matter escalated to a level that, according to sources, they were asked to step away from participation in the government organised AI Impact Summit 2026.

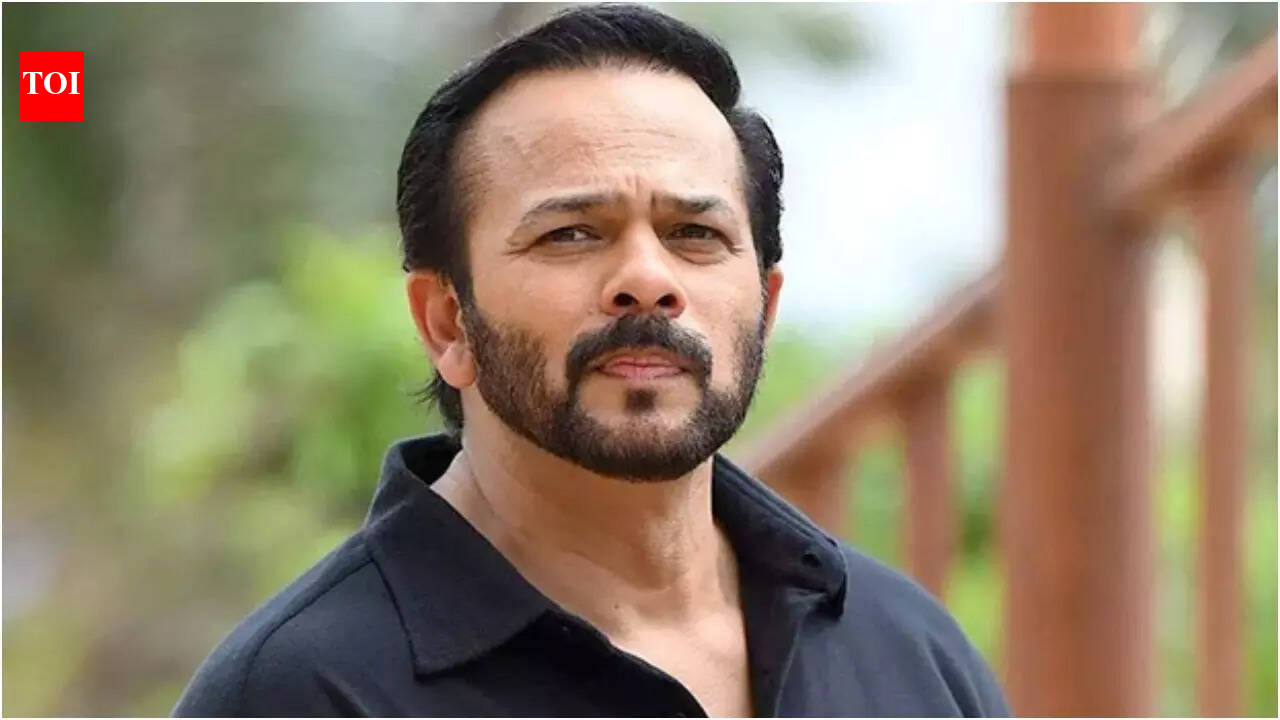

As the university came under scrutiny, its professors and deans from other departments are also facing examination. One such professor linked to the university is Professor Ravikant Kisana. Though he is currently serving as Dean of the School of Liberal Education and Languages at the university, the controversy around Galgotias has triggered a wider examination of the intellectual climate within the institution and the ideological positions of its faculty.

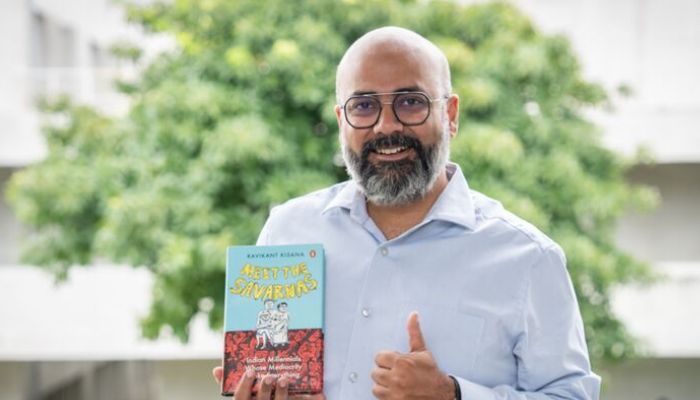

The dean who wrote ‘Meet the Savarnas’

Prof Ravikant Kisana publicly identifies as an Ambedkarite and OBC intellectual. He authored the 2025 book ‘Meet the Savarnas: Indian Millennials Whose Mediocrity Broke Everything’ and wrote a series of articles examining what he termed “Savarna culture”.

In the prologue of his book, he described elite savarnas as people “who critique everyone and everything but never themselves.” This was not presented as a critique of certain individuals or institutional behaviours. It was framed as a defining trait of a broad caste category.

Two lines from the book became especially controversial on social media are “Savarna marriages are inherently narcissistic” and “Savarna movements are inherently anti-democratic.”

Savarna marriages are inherently narcissistic.

— Gems of Indian Academia (@GemsofAcademia) February 18, 2026

Savarna movements are inherently anti-democratic.#Galgotias University's Dean, School of Liberal Education in his book "Meet The Savarnas" pic.twitter.com/opTAir0p1w

The use of the word “inherently” was striking. It suggested that narcissism and anti-democratic tendencies were intrinsic to marriages and movements of a particular caste group, not contingent on context, ideology or circumstance. Such framing moved beyond structural critique into essentialist characterisation.

When social analysis attributes moral or psychological qualities to an entire community, it risks replicating the very logic of collective judgement it claims to oppose.

From privilege analysis to civilisational indictment

The subtitle of the book itself declared that Savarna millennials’ “mediocrity broke everything.” In later chapters, Kisana wrote that Savarnas “inherited institutions and shrank them.” He portrayed Savarna dominance as responsible for stagnation in politics, academia, corporate life and civil society.

He repeatedly used the metaphor of a “glass floor” to argue that Savarnas remained structurally insulated even when they experienced anxiety. While examining structural privilege is a legitimate exercise, his language often implied that Savarna insecurity was exaggerated theatre rather than genuine experience.

The critique did not remain confined to institutional power structures. It extended into psychological terrain. Savarnas were portrayed as incapable of self-reflection, morally insulated and structurally resistant to democracy.

Structural inequality deserves serious scrutiny. But when an argument assigns inherent moral deficiency to a broad category of people, it invites the same kind of collective stereotyping that modern constitutional frameworks seek to transcend.

‘Shaadi like a Savarna’ and cultural disdain

In his article “Shaadi Like a Savarna”, Kisana examined elite weddings and described them as “the ultimate barometer for a deeply conservative and exclusionary Savarna social order.” He wrote that such weddings were performances of “power, pride and vanity” and suggested that even self-described progressive Savarna youth ultimately reverted to Brahmanical conservatism at the altar.

He contrasted these weddings with Satyashodhak marriages and framed Savarna cultural practices as hollow spectacle masking regressive caste mandates.

Critiquing caste endogamy and ritual hierarchy has been happening for a long time. However, describing the wedding culture of millions as intrinsically narcissistic and exclusionary did not distinguish between variation, reformist strands or changing social patterns. It treated an entire community’s cultural practices as fundamentally suspect.

Selective moral indictment of majority cultural expressions, while presenting others as inherently emancipatory, risks substituting one form of hierarchy for another.

‘Laughing like a Savarna’ and the morality of humour

In “Laughing Like a Savarna”, Kisana argued that Savarna humour historically relied on humiliating working class Bahujans. He described working class characters in Savarna comedy as treated like “humanoid appliances” and referred to what he called a “myth of eternal victimhood” embedded in Brahmanism.

The essay examined real problems in casteist humour. Yet it framed Savarna audiences collectively as participants in dehumanisation. The line between criticising harmful jokes and attributing moral corruption to an entire social group grew thin.

Humour that punches down deserves criticism. But describing a whole community’s comic culture as structurally rooted in humiliation risks flattening diversity within that community and overlooking internal dissent.

‘Dating like a Savarna’ and the psychology of purity

In “Dating Like a Savarna”, Kisana argued that caste mediated intimacy and desire in urban India. He described Savarna dating culture as a “secret language of aesthetics” and suggested that caste purity norms shaped even sexual behaviour. He wrote about what he termed the “glorification of Savarna semen” within Brahmanical discourse and argued that Savarna men occupied the apex of a social hierarchy in romantic spaces.

The essay claimed that there have been incidents of caste prejudice in relationships, including references to slurs and discriminatory behaviour. However, the broader framing again attributed structural psychological tendencies to Savarna individuals as a category.

When isolated instances of prejudice are presented as reflections of inherent collective psychology, the analysis shifts from examining discrimination to essentialising identity. If Kisana is to be believed, only Savarnas object to inter-caste marriages or relationships, which is an absolutely wrong notion.

The MBA critique and sweeping intellectual dismissal

In “A Long Overdue Love Letter to the Mediocrity of the Millennial Savarna MBAs and their Feckless Technobabble”, Kisana described millennial Savarna managers as “gormless” and “dull-witted” and accused them of bludgeoning public life with “aggressive loaded technobabble.”

He portrayed management education as “Brahmanised” and suggested that corporate stagnation in India stemmed from Savarna dominance. The language attributed intellectual mediocrity to a caste category rather than analysing specific policy failures or economic trends. Sweeping generalisation can energise polemic writing. It rarely strengthens scholarly rigour.

His position on UGC equity regulations

Kisana also strongly supported the UGC Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions Regulations, which were later put on hold by the Supreme Court.

In a post on X dated 25th January 2026, he described opposition to the regulations as “absolutely shameful outrage.”

absolutely shameful outrage on much-needed UGC regulations on campus caste discrimination– how many have died? how many dropped out/careers ruined? how many held accountable?

— Buffalo Intellectual (@ProfRavikantK) January 25, 2026

why so much pain when accountability is fixed? the regulations are not gift but a hard fought right!

On 27th January 2026, he wrote that it was “interesting to see Savarna media amplifying” criticism and compared it to Mandal era protests.

the irony is if the savarnas had been this upset & protested campus student suicides (and lack of accountability around it)– the UGC bill wouldnt have been needed in the first place.

— Buffalo Intellectual (@ProfRavikantK) January 27, 2026

In another post, he suggested that if SC, ST and OBC communities began mobilising, the situation could become “explosive quickly.”

stay on UGC regulations has emboldened casteist trolls, not placated them– Govt & courts are playing with fire here. if SC ST OBC samaaj starts mobilizing/responding in kind, it can become explosive quickly.

— Buffalo Intellectual (@ProfRavikantK) February 1, 2026

hope BJP has sense/power to reel this in, esp their online trolls.

In an article responding to the Supreme Court’s stay, he described Savarna protests as “virulent overreaction” and referred to “Savarna exceptionalism.”

Concerns raised about the regulations included questions of procedural balance, safeguards against misuse, and whether excluding general category students from the ambit of discrimination created asymmetry in protection. These concerns were dismissed by Kisana as caste-driven anxiety.

Debates on equity regulations must be calibrated between protecting vulnerable communities and ensuring due process. However, Kisana framed all apprehensions as reactionary backlash, downplaying the genuine concerns regarding the guidelines.

The responsibility of academic leadership

As Dean of the School of Liberal Education and Languages, Kisana shapes academic discourse and influences generations of students. Universities are expected to foster critical thinking and constitutional equality. When a senior academic repeatedly described marriages as “inherently narcissistic” and movements as “inherently anti-democratic” based on caste identity, questions naturally arose about the implications of such framing in classrooms.

While critique of caste hierarchy is an acceptable notion across sections of society in India, critique that essentialises rather than contextualises risks creating new binaries. One simply cannot continue to claim oppression and categorically sideline a community; otherwise, society cannot move forward with equality.

The controversy around Galgotias has brought attention to ideological positions that are shaping academic environments within the university. While Kisana’s ideological stance is being debated, what is undeniable is that his language in his books, as well as his articles and social media posts, is categorical, sweeping and deeply polarising.

India needs to move beyond inherited divisions, and to do so, the weight lies on the shoulders of academic leaders. It cannot be achieved if professors like Kisana continue to fill young minds with divisive ideologies.