Those who fear Babur should not guard Bharat’s culture

This piece is written as a direct response to the recent Op-Ed written by the Vice-Chancellor of Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication (MCNUJC) on OpIndia and a public letter issued by him, in which he chose to condemn my proposed session on Babur. While the tone of his intervention was framed as concern for “positivity” and cultural harmony, its substance reveals something far more troubling: a naïve; indeed dangerous, insistence that a civilisation can be strengthened by refusing to speak of its invaders. Such a position is not merely historically untenable; it stands in direct contradiction to the very ethos of Bharat. A civilisation that survives does not do so by selective silence, nor by outsourcing its memory to administrative convenience. It survives by remembering; clearly, honestly, and without fear. The pride in the word Bharat does not rest merely on civilisational continuity stretching back to the Battle of the Ten Kings. Its deeper source lies in something far more formidable: this civilisation did not fracture despite over a thousand years of continuous invasion. Many came, those who shattered Rome, extinguished Greece, humbled Persia, and erased entire worlds like Egypt. They broke civilisations elsewhere. They failed here. Bharat stood, bloodied, but unbroken. That endurance itself reflects the sacredness of this geography and the resilience of its civilisational soul. Dharma endured every test of time, perhaps because Charioteer Shri Krishna himself is our Bhagyavidhata. His words were not poetic musings. They strategic doctrines for the endurance of a civilisation when he uttered: यदा यदा हि धर्मस्य ग्लानिर्भवति भारत। अभ्युत्थानमधर्मस्य तदात्मानं सृजाम्यहम् ॥४-७॥ परित्राणाय साधूनां विनाशाय च दुष्कृताम् । धर्मसंस्थापनार्थाय सम्भवामि युगे युगे ॥४-८॥ The world, Krishna reminds us, is a perpetual battlefield against Adharma. He does not promise peace. Rather he promises return. Again and again. And he commands Arjuna not to retreat into moral paralysis, but to rise and fight for Dharma. I firmly believe the brave-hearts of Bharat took this command with absolute seriousness. They did not just believe in it. They acted upon it. They bore arms and waged war not for the sanctity of Krishna, Ram, Devi, and Mahadeva. Women chose jauhar over dishonour. Men fought until life itself was exhausted. Our ballads describe warriors whose bodies continued to battle even after being beheaded. One can be free to call it exaggeration, but it was no less than reverence for courage that transcended mortality. This bloodshed and self-immolation were not random acts of fanaticism. They were conscious sacrifices; for Dharma, for Bharat Mata, and for their Ishta. Against this backdrop, it is not merely ironic but deeply tragic when the Vice Chancellor, Shri Vinay Manohar Tiwari, says: “Instead of these, bringing a discussion on an invader like Babur to Bhopal is beyond comprehension, especially when Ayodhya is being illuminated on a path of faith and development. Under the New Education Policy, Babur and Aurangzeb are also being removed from history curricula. Then why do we wish to keep these ghosts of history alive in our discourse? This is the time to tell India’s own great epics, from the Ramayana to a national renaissance. The Prime Minister himself reiterates this again and again. In my view, at such a sensitive and energetically positive moment, placing an invader like Babur at the centre of discourse is not only foolish, but also entirely contrary to the current flow of India’s soul. At the very least, ideological rituals conducted with the support of the administration should have been kept free of this. Yet, regrettably, a shrill controversy has once again become associated with Bharat Bhavan. BLF used an author and his book as a shield to play this game within the sacred परिसर of Bharat Bhavan. This is intolerable.“ I am taken aback by the words of the Vice-Chancellor; not merely because they are historically shallow, but because they misrepresent the Prime Minister himself. Only days ago, the Prime Minister led the commemoration marking one thousand years since the first destruction of Somnath. On multiple occasions, including while speaking on Guru Parab, the Prime Minister has openly referred to the barbarity of Babur, to invasions, and to civilizational trauma. Very recently, even the National Security Advisor reaffirmed the importance of telling the stories of our gory past. These words are uttered by them as they care for the ethos of Bharat. A civilisation cannot be asked to celebrate itself while being instructed to forget its wounds. The calamities brought by invaders, forced conversions, sex slavery, mass slaughter, and cultural erasure are not rhetorical exaggerations; they are historical facts. K.S. Lal was not a naïve provocateur when he documented that nearly 80 million people were lost between 1000 and

This piece is written as a direct response to the recent Op-Ed written by the Vice-Chancellor of Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication (MCNUJC) on OpIndia and a public letter issued by him, in which he chose to condemn my proposed session on Babur. While the tone of his intervention was framed as concern for “positivity” and cultural harmony, its substance reveals something far more troubling: a naïve; indeed dangerous, insistence that a civilisation can be strengthened by refusing to speak of its invaders.

Such a position is not merely historically untenable; it stands in direct contradiction to the very ethos of Bharat. A civilisation that survives does not do so by selective silence, nor by outsourcing its memory to administrative convenience. It survives by remembering; clearly, honestly, and without fear.

The pride in the word Bharat does not rest merely on civilisational continuity stretching back to the Battle of the Ten Kings. Its deeper source lies in something far more formidable: this civilisation did not fracture despite over a thousand years of continuous invasion.

Many came, those who shattered Rome, extinguished Greece, humbled Persia, and erased entire worlds like Egypt. They broke civilisations elsewhere. They failed here. Bharat stood, bloodied, but unbroken. That endurance itself reflects the sacredness of this geography and the resilience of its civilisational soul.

Dharma endured every test of time, perhaps because Charioteer Shri Krishna himself is our Bhagyavidhata. His words were not poetic musings. They strategic doctrines for the endurance of a civilisation when he uttered:

यदा यदा हि धर्मस्य ग्लानिर्भवति भारत।

अभ्युत्थानमधर्मस्य तदात्मानं सृजाम्यहम् ॥४-७॥

परित्राणाय साधूनां विनाशाय च दुष्कृताम् ।

धर्मसंस्थापनार्थाय सम्भवामि युगे युगे ॥४-८॥

The world, Krishna reminds us, is a perpetual battlefield against Adharma. He does not promise peace. Rather he promises return. Again and again. And he commands Arjuna not to retreat into moral paralysis, but to rise and fight for Dharma.

I firmly believe the brave-hearts of Bharat took this command with absolute seriousness. They did not just believe in it. They acted upon it. They bore arms and waged war not for the sanctity of Krishna, Ram, Devi, and Mahadeva.

Women chose jauhar over dishonour. Men fought until life itself was exhausted. Our ballads describe warriors whose bodies continued to battle even after being beheaded. One can be free to call it exaggeration, but it was no less than reverence for courage that transcended mortality.

This bloodshed and self-immolation were not random acts of fanaticism. They were conscious sacrifices; for Dharma, for Bharat Mata, and for their Ishta.

Against this backdrop, it is not merely ironic but deeply tragic when the Vice Chancellor, Shri Vinay Manohar Tiwari, says:

“Instead of these, bringing a discussion on an invader like Babur to Bhopal is beyond comprehension, especially when Ayodhya is being illuminated on a path of faith and development. Under the New Education Policy, Babur and Aurangzeb are also being removed from history curricula. Then why do we wish to keep these ghosts of history alive in our discourse? This is the time to tell India’s own great epics, from the Ramayana to a national renaissance. The Prime Minister himself reiterates this again and again.

In my view, at such a sensitive and energetically positive moment, placing an invader like Babur at the centre of discourse is not only foolish, but also entirely contrary to the current flow of India’s soul. At the very least, ideological rituals conducted with the support of the administration should have been kept free of this. Yet, regrettably, a shrill controversy has once again become associated with Bharat Bhavan. BLF used an author and his book as a shield to play this game within the sacred परिसर of Bharat Bhavan. This is intolerable.“

I am taken aback by the words of the Vice-Chancellor; not merely because they are historically shallow, but because they misrepresent the Prime Minister himself.

Only days ago, the Prime Minister led the commemoration marking one thousand years since the first destruction of Somnath. On multiple occasions, including while speaking on Guru Parab, the Prime Minister has openly referred to the barbarity of Babur, to invasions, and to civilizational trauma. Very recently, even the National Security Advisor reaffirmed the importance of telling the stories of our gory past. These words are uttered by them as they care for the ethos of Bharat.

A civilisation cannot be asked to celebrate itself while being instructed to forget its wounds. The calamities brought by invaders, forced conversions, sex slavery, mass slaughter, and cultural erasure are not rhetorical exaggerations; they are historical facts. K.S. Lal was not a naïve provocateur when he documented that nearly 80 million people were lost between 1000 and 1500 CE during Islamic invasions.

The celebration of Bharat is incomplete, indeed dishonest, without remembering those who sacrificed so that I may still wear the Raksha Sutra and the Tilak. One cannot speak of Shri Ram while sanitising the ferocity of Ravan. To do so is intellectual fraud.

This selective amnesia is precisely the legacy of Nehruvian historiography, which chose to suppress historical wrongs in the name of a contrived positivity and a manufactured idea of Hindu–Muslim unity. The result has been a prolonged civilizational Stockholm syndrome, where the victim is trained to apologise for remembering.

I write this on the day we commemorate thirty-six years since the exodus of Kashmiri Hindus. Even today, there are voices claiming that “nothing really happened” in Kashmir. That denial exists because the past was sanitised, its horrors pushed under the carpet.

How does one stand at Martand Mandir, one of the most sacred sites of Kashmir, and not acknowledge that every surviving Muslim demographic there is a reminder of a Hindu civilisation that was systematically erased? This is not rhetoric. It is a historical truth. Kashmir was a Hindu land, home to multiple sampradayas, including Buddhist traditions. Under the guidance of figures like Sufi Hamdani, forced conversions transformed that landscape, leading to the near-vanishing of Kashmiri Hindus.

If we cannot speak this truth aloud, then what exactly are we preserving?

There are countless such histories that must be spoken; from mandirs and from every sacred geography of Bharat, to honour the promise made by generations of Kshatriyas who sacrificed themselves for the motherland.

What is even more disturbing is that the Vice-Chancellor today sounds less like an academic and more like a spokesperson for those who were intellectually dishonest from the very beginning; those who falsely reported that the Bhopal Literature Festival was hosting a session to “glorify Babur.” They did not bother to read even a single page of my book.

The protest was staged on a false premise. Threats were issued, of burning books, of disrupting the event, of physical harm. Faced with legitimate security concerns, the organisers cancelled my session. Let us call it what it was: a de facto ban.

Does the Vice-Chancellor understand that I had security concerns? Does he understand that I came to Bhopal to discuss my own book, not to provoke anyone? And yet he makes statements suggesting that the festival was merely “using” me; as though my cancellation were a political tactic rather than an act of intimidation.

Politics can wait. Intellectual honesty cannot.

To compound this farce, Swadesh published a piece boasting that it had ensured the “triumph of culture and dharma” by preventing my session. One must ask: what kind of world are we inhabiting? In the process, they have turned Hindutva itself into a laughing stock.

Today, media portals openly speak of the Right devouring itself. Headlines mock, “Babur haunts…”. The damage is done.

The irony is brutal: for generations to come, it will be remembered that those draped in saffron could not even stand by one of their own, someone was vilified without being read, was silenced without being heard.

Why does he believe that merely stating he has authored a book on “Islamic Rule in Hindustan” somehow legitimises his stance in condemning my session?

I am certain this is not jealousy. Yet by invoking his authorship as a moral shield, he leaves precisely that aftertaste, of an author unsettled by another scholar working on the same civilisational fault line. A reality check, however, is necessary.

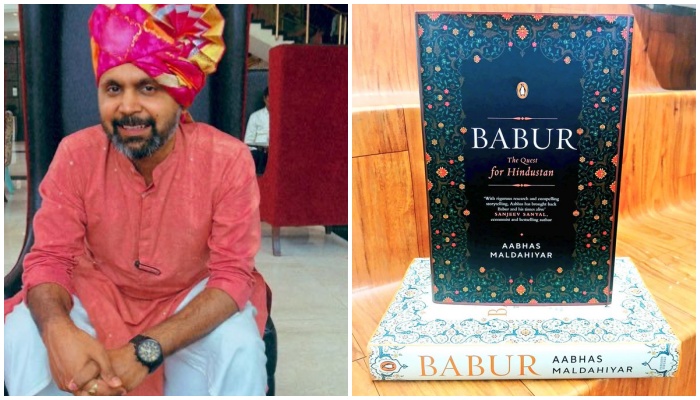

His work is largely derivative, grounded in the magnum opus of Elliot and Dowson, which itself relies on selective translations of Muslim chroniclers. My approach has been fundamentally different; and deliberately so. I followed the methodological path recommended by Sir Jadunath Sarkar in his 1953 retirement address: to engage original sources in the language of authority.

Across Babur–I and Babur–II, I have produced nearly one thousand pages based on direct engagement with Persian manuscripts. I have pointed out inaccuracies and interpretative distortions in the translations of Annette Susannah Beveridge, and others. One may state that this was an act of polemics, but the truth is, I was reading the original manuscripts alongside the translations and fallacies (inconsistencies) were easy to find.

By stating so, I’m not making any claim of superiority. Rather I’m just elaborating the statement of method adopted by me which was suggested as the “way” to deal with history by veteran, Sarkar.

When the national debate on Babur resurfaced following NCERT changes, I was among the very few historians, apart from RC Majumdar and Sir Jadunath Sarkar, who were publicly referenced as part of the so-called “Nationalist-wing” scholarly tradition. When people now claim that the Right produces no scholars, it is precisely because individuals occupying decorated offices lend credibility to such lazy generalisations. Perhaps you wish to gatekeep words of Nationalists on invaders only to give more opportunity to distortion creators like Audrey Truschkey.

If he believes I had no reason to protest, if he feels my letter to the Prime Minister was unnecessary, then I can only pity the intellectual poverty of that position. Perhaps only among all politicians, Narendra Modi understands at best how grotesque it is to censor discussion on invaders, because he himself spoke openly about Islamic invasions while commemorating one thousand years of the destruction of Somnath, and he did so from the sacred precincts of Somnath itself.

To invoke the Prime Minister as a shield for silencing discourse on Babur is therefore intellectually dishonest and outright absurd.

I regard Bharat Bhavan as one of the most significant cultural institutions of Bharat. For me, it is no less than a temple. I studied that complex closely during my undergraduate training in architecture. Designed by Charles Correa, it is a sacred spatial expression of Indian civilisational memory. I can state with confidence that I have treated Bharat Bhavan with greater reverence since the age of seventeen than many office bearers who now posture as its custodians.

And precisely because of that sanctity, there could have been no better place to speak about the forged “Bhopal Wasiyatnama”, the so-called Will of Babur, used repeatedly to paint him as a paragon of tolerance. That was the core subject of my session.

There could have been no better place to discuss a book that is perhaps the only one in the world dedicated to the brave women of Chanderi (Madhya Pradesh), who committed jauhar five centuries ago; after which Babur declared the region Dar-ul-Harb cleared and Dar-ul-Islam established.

There could have been no better place to speak of the valour symbolised by bangles, of Shakti, because without recognising that valour, all hollow invocations of “culture and tradition” are meaningless. These women did not leap into fire for some pointless posturing. They did so for the Dharma.

But such truths are inconvenient when politics colonises the mind; when culture becomes a fashionable slipper one drags around while loudly proclaiming, “I walk culture.”

And what did Swadesh do when I protested? It stooped to character assassination. It dredged up my Marxist phase, which actually existed from 2008–2012, a four-year period, constituting barely nine percent of my life; and used it to allege opportunism. What it concealed was that for the last thirteen years, over thirty percent of my lived life, I have worked consistently as a Hindutva ideologue, almost my entire adult life.

Only a wilfully ignorant analyst; or a propagandist would employ such dishonest arithmetic.

I continue to practise as an architect, working twelve hours a day. In parallel, I taught myself Persian to access original manuscripts. Writing detailed historical works grounded in primary sources is not how one becomes a “poster boy.” It is how one attempts to become a scholar.

Then came his letter (of the VC); sanctimonious, evasive, soaked in “Ishwar–Allah Tero Naam” sentimentality, while cloaking itself in concern for the Ramayana. Mahatma Gandhi too invoked Ram Rajya with pacifism. That is precisely the tone this letter carried.

But how does one speak of the Ramayana and omit the Ram–Ravan Yuddha? Will Ravan be erased as well in the name of “positivity”?

In conclusion, I can only add that Bharat Bhavan is not merely an arts centre. It is a civilisational space that must echo the spirit articulated by Shri Krishna and Bhagwan Ram, the centrality of Kshatriya Dharma. And Kshatriya Dharma is meaningless without Shatrubodh, the clarity to recognise the enemy.

The Vice-Chancellor could have taken a principled stand. Instead, he has chosen politics over truth. History will remember that choice.

And regrettably, it will remember him among those who feared Babur.