Tribal villages can bar entry of missionaries: Read how SC rejected Colin Gonsalves’ plea and upheld Chhattisgarh HC’s stand amid rampant forced conversions

There is no alternative way to express the acute plague of religious conversion that has invaded the country. Even the most remote areas are not immune to the deceptive enticements of Christian missionaries who employ various tactics to compel the people to forsake their indigenous beliefs in favour of a foreign faith. Hence, some tribal villages of Chhattisgarh, weary of this malicious agenda, resorted to enforcing restrictions on the entry of these missionaries and pastors. Notably, the issue was initially brought before the Chhattisgarh High Court and subsequently to the Supreme Court. However, both courts dismissed the petition by Digbal Tandi from the Kanker district, challenging the imposed restrictions. The matter stemmed after resolutions were adopted by Gram Sabhas and hoardings were placed in Scheduled Areas warning against the activities of religious conversion. The decision was made by 8 tribal villages of the Kanker district, including Habechur, Musurputta, Sulagi, Parvi, Junwani, Ghota, Ghotiya and Kudal. The locals set up boards that conveyed that the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas Act barred the arrival of Christian priests and pastors. The Supreme Court effectively stands with the high court’s order On 16th February (Monday), a bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Justice Sandeep Mehta refused to overrule the Chhattisgarh High Court’s judgement, which had made specific observations regarding conversions carried out through coercion and deceit, as well as their effects on social harmony, along with tribal cultural identity. Tandi was represented by senior counsel Colin Gonsalves, who alleged that the high court passed general and unfavourable statements about Christian missionary work without any supporting documentation. He insisted that the high court’s remarks on conversions were outside the purview of the petition, and the subject at hand was also limited. According to Gonsalves, the apex court is currently considering a case involving more than “700 assaults” on pastors during prayer sessions. Additionally, he cited cases in which tribals who embraced Christianity were supposedly refused the right to be buried in their hamlets. Gonsalves then pointed to another case and contended that the bodies of converted tribal individuals laid to rest in villages were being unearthed. He added that throughout the previous ten years, not a single conviction had occurred under the state’s conversion law. “You can’t stop me from doing my Sunday prayer meeting and the high court says it’s not unconstitutional,” he stated, claiming wider ramifications because of its comments. On the other hand, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, who argued on behalf of the Chhattisgarh government, retorted that several submissions made before the bench were not included in the initial pleadings heard by the high court. He highlighted that the high court’s case was limited to the removal of hoardings and the petitioners had been instructed to contact the relevant Gram Sabhas. The bench noted that the writ petition before the high court was strictly focused and concurred with the state’s stance. “Gonsalves, please see the writ petition before the high court and the relief claimed. You have been asked to go to the Gram Sabhas,” the justices pronounced. The Supreme Court firmly sided with the high court’s verdict and rejected the plea. Chhattisgarh HC ruled in support of protecting the interests of indigenous tribes On 28th October (Tuesday) of last year, the Chhattisgarh High Court refused to stop the residents of the 8 villages from erecting hoardings to stop forcible or fraudulent conversions. A bench of Chief Justice Ramesh Sinha and Justice Bibhu Datta Guru decided that hanging signs warning tribal members against illicit conversions cannot be considered unlawful. They turned down the petition that called for the hoardings to be taken down in the name of discrimination against Christian pastors and converts by banning their admission into the communities. Tandi accused the Christian community and its religious leaders of being separated from the rest of the population. Furthermore, the plea charged that the Panchayat Department directed the Zila and Janpad panchayats alongside the Gram panchayat to introduce a resolution labelled “Hamari Parampara Hamari Virasat (Our tradition, our heritage)” that blocked pastors and converted Christians from the village. “No material has been placed on record to indicate that the circular authorises discrimination against any religious group,” the court countered. It similarly declared that nothing in the hoardings could be construed as discriminatory against Christians and only excluded specific pastors from entering if they planned to host religious conversion events. The court concluded that neither the hoardings nor the Panchayat Department circular included any indications of bias against the Christian community and observed, “

There is no alternative way to express the acute plague of religious conversion that has invaded the country. Even the most remote areas are not immune to the deceptive enticements of Christian missionaries who employ various tactics to compel the people to forsake their indigenous beliefs in favour of a foreign faith.

Hence, some tribal villages of Chhattisgarh, weary of this malicious agenda, resorted to enforcing restrictions on the entry of these missionaries and pastors. Notably, the issue was initially brought before the Chhattisgarh High Court and subsequently to the Supreme Court. However, both courts dismissed the petition by Digbal Tandi from the Kanker district, challenging the imposed restrictions.

The matter stemmed after resolutions were adopted by Gram Sabhas and hoardings were placed in Scheduled Areas warning against the activities of religious conversion. The decision was made by 8 tribal villages of the Kanker district, including Habechur, Musurputta, Sulagi, Parvi, Junwani, Ghota, Ghotiya and Kudal. The locals set up boards that conveyed that the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas Act barred the arrival of Christian priests and pastors.

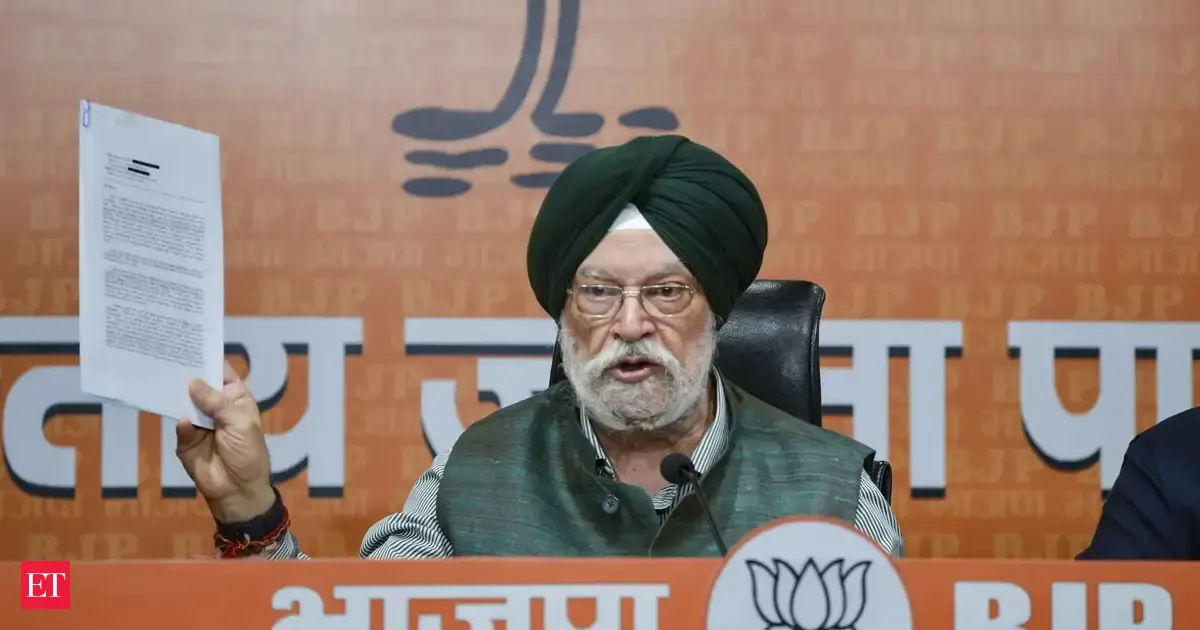

The Supreme Court effectively stands with the high court’s order

On 16th February (Monday), a bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Justice Sandeep Mehta refused to overrule the Chhattisgarh High Court’s judgement, which had made specific observations regarding conversions carried out through coercion and deceit, as well as their effects on social harmony, along with tribal cultural identity.

Tandi was represented by senior counsel Colin Gonsalves, who alleged that the high court passed general and unfavourable statements about Christian missionary work without any supporting documentation. He insisted that the high court’s remarks on conversions were outside the purview of the petition, and the subject at hand was also limited.

According to Gonsalves, the apex court is currently considering a case involving more than “700 assaults” on pastors during prayer sessions. Additionally, he cited cases in which tribals who embraced Christianity were supposedly refused the right to be buried in their hamlets.

Gonsalves then pointed to another case and contended that the bodies of converted tribal individuals laid to rest in villages were being unearthed. He added that throughout the previous ten years, not a single conviction had occurred under the state’s conversion law. “You can’t stop me from doing my Sunday prayer meeting and the high court says it’s not unconstitutional,” he stated, claiming wider ramifications because of its comments.

On the other hand, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, who argued on behalf of the Chhattisgarh government, retorted that several submissions made before the bench were not included in the initial pleadings heard by the high court. He highlighted that the high court’s case was limited to the removal of hoardings and the petitioners had been instructed to contact the relevant Gram Sabhas.

The bench noted that the writ petition before the high court was strictly focused and concurred with the state’s stance. “Gonsalves, please see the writ petition before the high court and the relief claimed. You have been asked to go to the Gram Sabhas,” the justices pronounced. The Supreme Court firmly sided with the high court’s verdict and rejected the plea.

Chhattisgarh HC ruled in support of protecting the interests of indigenous tribes

On 28th October (Tuesday) of last year, the Chhattisgarh High Court refused to stop the residents of the 8 villages from erecting hoardings to stop forcible or fraudulent conversions. A bench of Chief Justice Ramesh Sinha and Justice Bibhu Datta Guru decided that hanging signs warning tribal members against illicit conversions cannot be considered unlawful.

They turned down the petition that called for the hoardings to be taken down in the name of discrimination against Christian pastors and converts by banning their admission into the communities. Tandi accused the Christian community and its religious leaders of being separated from the rest of the population.

Furthermore, the plea charged that the Panchayat Department directed the Zila and Janpad panchayats alongside the Gram panchayat to introduce a resolution labelled “Hamari Parampara Hamari Virasat (Our tradition, our heritage)” that blocked pastors and converted Christians from the village.

“No material has been placed on record to indicate that the circular authorises discrimination against any religious group,” the court countered. It similarly declared that nothing in the hoardings could be construed as discriminatory against Christians and only excluded specific pastors from entering if they planned to host religious conversion events.

The court concluded that neither the hoardings nor the Panchayat Department circular included any indications of bias against the Christian community and observed, “The hoardings appear to have been installed by the concerned Gram Sabhas as a precautionary measure to protect the interests of indigenous tribes and local cultural heritage.”

It ordered the petitioner to first exhaust all other legislative remedies, as he had not used any of them before approaching the court. “A party must firstly exhaust the statutory alternative remedy available before approaching the high court seeking redressal of any grievance,” the bench mentioned.

The judges outline how poor SC/ST people are trapped, leading to “cultural coercion” through conversion

The judges recognised that extensive religious conversions undermine social cohesion and compromise the traditional character of tribals. They explained that missionary organisations have been evangelising and pushing unbelievers to become Christians under the guise of social assistance.

The court remarked, “Missionary activity in India dates back to the colonial period, when Christian organisations established schools, hospitals and welfare institutions. Initially, these efforts were directed at social upliftment, literacy and health care.”

“However, over time, some missionary groups began using these platforms as avenues for proselytisation. Among economically and socially deprived sections, especially the Scheduled Tribes and the Scheduled Castes, this led to a gradual religious conversion under the promise of better livelihoods, education, or equality,” it highlighted.

The court emphasised how the conversions of the poor and illiterate cause division in tribal groups and are tantamount to “cultural coercion.” It noted, “In remote tribal belts, missionaries are often accused of targeting illiterate and impoverished families, offering them monetary aid, free education, medical care, or employment in exchange for conversion. Such practices distort the spirit of voluntary faith and amount to cultural coercion.”

The bench conveyed, “This process has also led to deep social divisions within tribal communities, distancing them from traditional rituals and communal festivals. As a result, villages become polarised, leading to tension, social boycotts and sometimes even violent clashes.”

Religious freedom is not absolute, and it does not allow targeting of the vulnerable populace

The court clarified that religious freedom as guaranteed by Article 25 of the Constitution is not unqualified and is governed by morals, public order and health. It underscored that anti-conversion laws have been imposed by multiple state governments because the right is vulnerable to abuse.

“India’s secular fabric thrives on coexistence and respect for diversity. Religious conversion, when voluntary and spiritual, is a legitimate exercise of conscience. However, when it becomes a calculated act of exploitation disguised as charity, it undermines both faith and freedom,” the judges expressed.

“The so-called ‘conversions by inducement’ by certain missionary groups is not merely a religious concern. It is a social menace that threatens the unity and cultural continuity of India’s indigenous communities. The remedy lies not in intolerance, but in ensuring that faith remains a matter of conviction, not compulsion,” they added.

Chhattisgarh continues to grapple with rampant Christian conversion

India is currently tackling the sensitive issue of forced conversions, whether under the pretext of love jihad or through the inducements offered by Christian missionaries in various regions of India, and Chhattisgarh is not exempt from this challenge. Christian missionaries have been regularly involved in unauthorised endeavours in the state, pressurising people to embrace their religion.

A similar case was launched after a prayer meeting in a village under the jurisdiction of the Katghora police station in the Korba district of Chhattisgarh in December 2025. The gathering, which was organised by Christian community members in an open field, targeted sick and impoverished people, childless couples, sparking complaints from the locals and police intervention.

According to locals, several outsiders joined the conference and focused on vulnerable groups in society, such as the sick, childless couples and low-income families. They mentioned that it was announced that prayers could cure illnesses and eliminate suffering. The attendees were encouraged and asked to convert for spiritual healing.

Last November, another episode of illegal conversion surfaced when some Hindu women and children were discovered participating in a Christian prayer within a home in the Chilhati village near the Sarkanda police station in the Bilaspur district of the state. Afterwards, Hindu activists rushed there with a loudspeaker to warn people of the Christian prayer meet. According to Kanhaiya Sahu, a member of a Hindu outfit, he was informed that a residence on the village’s Shandi Mandir road was utilised to seduce Hindus to become Christians.

It was then reported that there have been over 38 such incidents in many places, including Civil Lines, Sarkanda, Koni, Sakri, Torwa, Masturi, Sipat and Pachpedi, over the past six months. Two distinct cases of religious conversion were previously filed in the Sarkanda and Pachpedi police station regions on 12th November.

Moreover, a new trend of religious conversion came to light in different regions of Chhattisgarh a month earlier, where female preachers, commonly known as “lady missionaries,” offer a sympathetic ear to widows, daily wage workers and economically disadvantaged women before inviting them to “Changai Sabhas” (healing prayer gatherings) and promising to alleviate their problems.

According to investigations, women and young girls, including 3 to 14 years of age, are convinced to become Christians during these events through spiritual rites and emotional appeals. They are gently exposed to church operations and repeatedly indoctrinated that prayer is the only way to end their pain.

Women are invited to fill out forms at the churches, promising to regularly attend Sunday prayers and to trust that God is going to take care of their health issues and other struggles. The preachers then attribute any improvement in health to “the Lord’s blessings,” even though contemporary medications are frequently employed in these situations.

The majority of these converts do not legally assume Christian names or become nuns; rather, they remain in their communities with their previous Hindu names and identities while clandestinely promoting the religion. Thus, they can stay out of the public eye and continue to exploit government privileges like caste-based reservations.

A June report from that year unveiled that there has been a significant shift in the religious makeup of the residents in numerous districts of Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, especially in tribal areas, during the past few decades. The figures even indicated an increase by 41% in several districts.

The infected lesion of Christian conversion

The aforesaid occurrences do not even begin to address the extent of the conversion racket, which is outlined by The Joshua Project, a Christian conversion “research” program. It boasted of converting 24 lakh individuals each year in 2024. The group is behind a conversion network in Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha and Chhattisgarh, reaching 60 million individuals in its extensive campaign.

The outrageous claims made by these missionaries or pastors might appear humorous and offer ample content for meme creators on social media, however, the reality is that their actions carry grave consequences on the ground, affecting not only the Hindu demographic and infringing upon the rights of the SC/ST communities through Dalit conversions but also posing a glaring threat to national security, as was recently witnessed in Rajasthan.

German couple, Swain Boz Bet Jaler and Sandra, as well as others, were arrested for manipulating people to become Christians by tempting them with money in the Sri Ganganagar district. An unlicensed church was running in a rental home with the assistance of foreigners in the city that borders Pakistan. Derogatory remarks were also made about Hindu gurus and deities in an attempt to push people towards Christianity.

Most importantly, the couple travelled to the Majhiwala border, which prompted a security alert in the area to counter any unfortunate incident. Sri Karanpur is a sensitive region where strict regulations control the movement of foreign nationals. However, the duo entered there without permission and secretly organised a religious gathering.

Is it feasible for a vulnerable nation such as India, which is destined to share borders with hostile adversaries like Pakistan, to allow such individuals within its territory, thereby jeopardising national security and endangering the lives of thousands of people?

Can “religious liberity”, which has been repeatedly defined as not absolute by not only high courts but also the apex court, and certainly does not involve conversion, be permitted to risk national security? Additionally, how can the same be limited to Christians who wish to convert, while Hindus who are simply trying to resist are overlooked?

These elements, despite their faults, should not be exposed to violence, but why is a peaceful hoarding being contested following the high court judgement? The fact was also pointed out by the Solicitor General. It only provides a legitimate warning to undesirable entities that might disturb the harmony in their regions. In what way is that controversial, or should Christian missionaries be awarded the ultimate freedom to instigate even more disorder and unrest in Indian society?

Conclusion

If persuading others to abandon their beliefs via financial incentives and bogus promises only to convert to Christianity is marketed as “religious freedom,” then the impacted parties likewise possess the right to devise their own methods to safeguard themselves from this threat. There cannot be any ambiguity regarding this.

The assertion of segregation or isolation presented in such cases is equally hollow. Isn’t the segregation already evident both in name and spirit once a person decides to sever ties with the faith and culture that linked them to the mainstream? Why strive to masquerade as part of a community that has already been relinquished? Or the underlying motive is to turn even the furthest corner into a deracinated centre where people only seem native on the surface while everything else has been washed away in the tide of an Abrahamic faith?