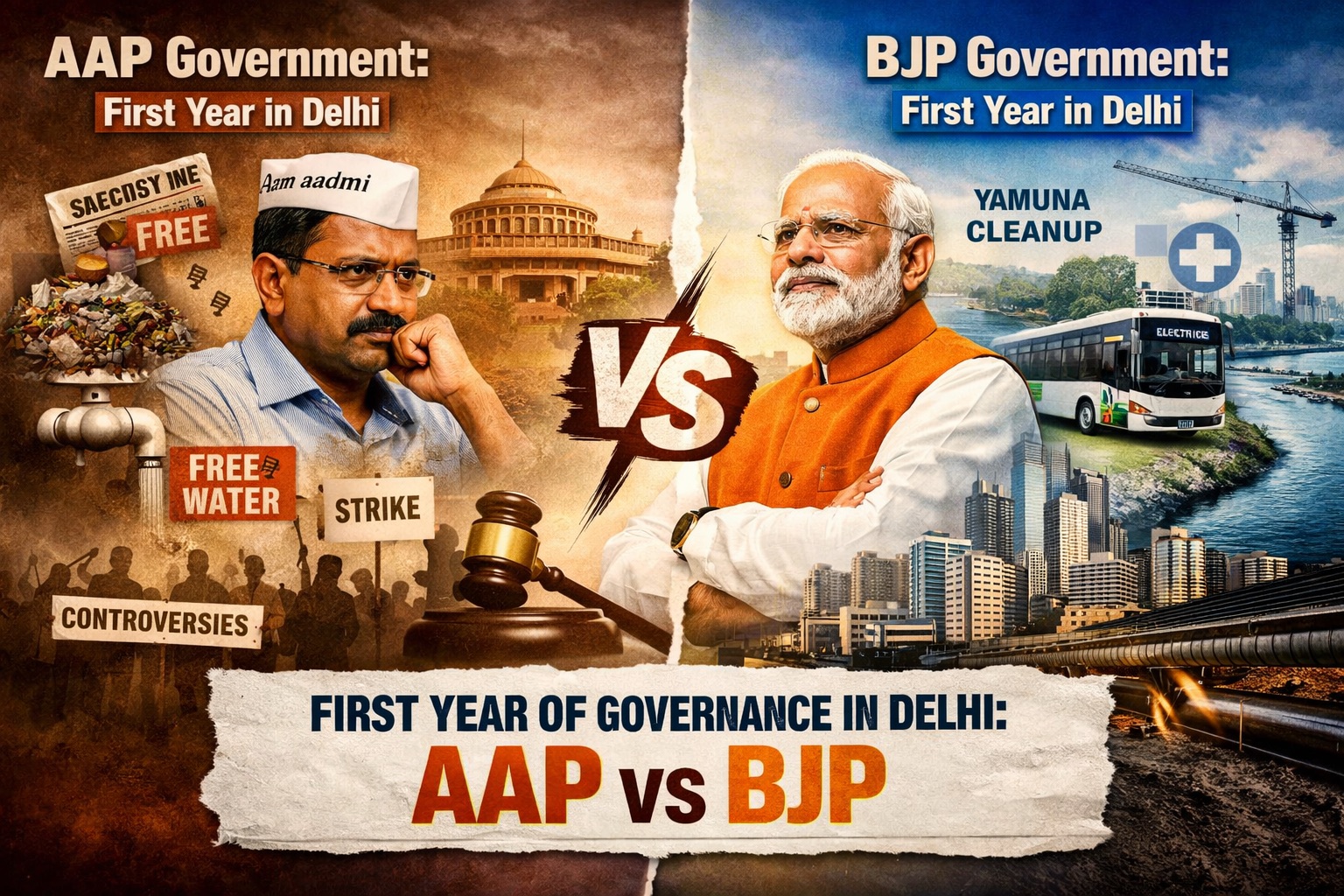

1 year of the BJP govt in Delhi: A governance shift from AAP’s subsidy politics to structural development

Recently, the BJP government in Delhi completed its first year in office, marking an important milestone that naturally invites public evaluation of its governance and delivery. Over the past few days, the Aam Aadmi Party and its social media ecosystem have launched a political offensive, trying to portray the current administration as ineffective and lacking in delivery. This coordinated attack, echoed by party workers, aims to change the public image of the BJP’s governance in a relatively short time. However, such assertions call for an objective analysis of the AAP’s own performance since it took power in February 2015 with a historic mandate of 67 out of 70 seats, one of the most decisive electoral victories in Delhi’s political history. Back in 2015, AAP presented itself as a transformative political force promising corruption-free governance, administrative transparency, and systemic reform. Its first year was widely promoted through campaigns such as #1YearofHonestPolitics and “Ek saal Bemisaal”, projecting an image of clean and effective governance. Aside from Political campaigning, the period was characterised by significant subsidy expansion, institutional tensions, internal party revolt, administrative disturbances, and a number of controversies that gained widespread notice. As political narratives resume dominance in public discourse following the BJP government’s one-year anniversary, it is critical to examine the AAP’s own first-year governance record in order to distinguish between political projection and administrative reality. Subsidy-driven governance model of AAP After assuming office in February 2015, one of the first major decisions was to implement large-scale consumer subsidies to fulfil electoral promises. The AAP government introduced free water of up to 20,000 litres per household per month and free electricity of up to 200 units, along with a 50% subsidy for 201-400 units. These initiatives provided immediate financial relief to consumers and became integral to the party’s governance model and electoral discourse. However, the fiscal implications of these initiatives were immediate and significant. Delhi’s subsidy expenditure increased by more than 600%, from Rs. 1,554.72 crore in 2014-15 to Rs.10,995.34 crore in 2024-25. The power subsidy increased from Rs. 291.94 crore in 2014-15 to Rs. 1,442.76 crore within a year of the AAP taking office, and then to Rs. 3,600.50 crore. Similarly, subsidy support for the Delhi Jal Board increased from Rs. 20.83 crore to Rs. 500 crore during the same period. The rapid development mirrored a governance style that relied on recurring subsidies rather than structural reforms of public utilities, posing long-term questions about fiscal sustainability and institutional financial stability. These types of governance are comparable to a glittering facade, visually appealing and politically lucrative in the short term, but structurally weak, with long-term implications for budgetary health and governing ability. Administrative failures and governance crisis Along with the implementation of a subsidy-driven model, the Aam Aadmi Party government’s first year was marked by significant administrative disruptions and governance issues. One of the most obvious crises was the sanitation workers’ strike. In April 2015, sanitation workers across East and North Delhi went on strike due to unpaid salaries. The strike lasted nearly two weeks, resulting in significant garbage piling up across roads, residential colonies and public areas. It raised concerns about the health emergency. Although the Delhi government approved a loan of ₹551 crore to municipal organisations, the crisis highlighted deficiencies in financial planning and administrative cooperation. The severity of the problem became known when the Delhi High Court intervened, forcing the Delhi government to release adequate funds to pay sanitation workers’ salary arrears. The court cautioned that the continuous disruption of rubbish collection services could lead to an epidemic. After this intervention, the Lt Governor approved releasing ₹493 crore to municipal corporations to fix the situation. The Kejriwal government’s first year was also marked by a protected institutional conflict with the Lieutenant Governor’s office and the central government over administrative power and appointments. These disputes developed over fundamental governance issues, including the selection of the chief secretary, control of the Anti-Corruption Bureau, and administrative authority over top officials. These disagreements resulted in a series of high-profile episodes, including police action against AAP MPs and a CBI raid on the Chief Minister’s Principal Secretary’s office in December 2015. Such developments created an atmosphere in which governance and administrative functioning were frequently eclipsed by political and institutional conflict, raising concerns about the government’s stabilit

Recently, the BJP government in Delhi completed its first year in office, marking an important milestone that naturally invites public evaluation of its governance and delivery. Over the past few days, the Aam Aadmi Party and its social media ecosystem have launched a political offensive, trying to portray the current administration as ineffective and lacking in delivery. This coordinated attack, echoed by party workers, aims to change the public image of the BJP’s governance in a relatively short time. However, such assertions call for an objective analysis of the AAP’s own performance since it took power in February 2015 with a historic mandate of 67 out of 70 seats, one of the most decisive electoral victories in Delhi’s political history.

Back in 2015, AAP presented itself as a transformative political force promising corruption-free governance, administrative transparency, and systemic reform. Its first year was widely promoted through campaigns such as #1YearofHonestPolitics and “Ek saal Bemisaal”, projecting an image of clean and effective governance. Aside from Political campaigning, the period was characterised by significant subsidy expansion, institutional tensions, internal party revolt, administrative disturbances, and a number of controversies that gained widespread notice. As political narratives resume dominance in public discourse following the BJP government’s one-year anniversary, it is critical to examine the AAP’s own first-year governance record in order to distinguish between political projection and administrative reality.

Subsidy-driven governance model of AAP

After assuming office in February 2015, one of the first major decisions was to implement large-scale consumer subsidies to fulfil electoral promises. The AAP government introduced free water of up to 20,000 litres per household per month and free electricity of up to 200 units, along with a 50% subsidy for 201-400 units.

These initiatives provided immediate financial relief to consumers and became integral to the party’s governance model and electoral discourse. However, the fiscal implications of these initiatives were immediate and significant. Delhi’s subsidy expenditure increased by more than 600%, from Rs. 1,554.72 crore in 2014-15 to Rs.10,995.34 crore in 2024-25. The power subsidy increased from Rs. 291.94 crore in 2014-15 to Rs. 1,442.76 crore within a year of the AAP taking office, and then to Rs. 3,600.50 crore. Similarly, subsidy support for the Delhi Jal Board increased from Rs. 20.83 crore to Rs. 500 crore during the same period.

The rapid development mirrored a governance style that relied on recurring subsidies rather than structural reforms of public utilities, posing long-term questions about fiscal sustainability and institutional financial stability. These types of governance are comparable to a glittering facade, visually appealing and politically lucrative in the short term, but structurally weak, with long-term implications for budgetary health and governing ability.

Administrative failures and governance crisis

Along with the implementation of a subsidy-driven model, the Aam Aadmi Party government’s first year was marked by significant administrative disruptions and governance issues. One of the most obvious crises was the sanitation workers’ strike. In April 2015, sanitation workers across East and North Delhi went on strike due to unpaid salaries. The strike lasted nearly two weeks, resulting in significant garbage piling up across roads, residential colonies and public areas. It raised concerns about the health emergency. Although the Delhi government approved a loan of ₹551 crore to municipal organisations, the crisis highlighted deficiencies in financial planning and administrative cooperation. The severity of the problem became known when the Delhi High Court intervened, forcing the Delhi government to release adequate funds to pay sanitation workers’ salary arrears. The court cautioned that the continuous disruption of rubbish collection services could lead to an epidemic. After this intervention, the Lt Governor approved releasing ₹493 crore to municipal corporations to fix the situation.

The Kejriwal government’s first year was also marked by a protected institutional conflict with the Lieutenant Governor’s office and the central government over administrative power and appointments. These disputes developed over fundamental governance issues, including the selection of the chief secretary, control of the Anti-Corruption Bureau, and administrative authority over top officials. These disagreements resulted in a series of high-profile episodes, including police action against AAP MPs and a CBI raid on the Chief Minister’s Principal Secretary’s office in December 2015. Such developments created an atmosphere in which governance and administrative functioning were frequently eclipsed by political and institutional conflict, raising concerns about the government’s stability and effective policy implementation during its critical first year.

Controversies and credibility questions

The Aam Aadmi Party rose to power on the promise of clean governance and ethical political behaviour. However, its first year was marked by several controversies and allegations involving senior leaders and government officials. It raised serious concerns about trustworthiness and internal accountability. In June 2015, Delhi Police arrested then law minister Jitendar Singh Tomar on allegations of owning a forged degree. The episode forced his departure and showed the reality of an anti-corruption government whose whole narrative was to remove the corrupt politician. Eventually, it became the same part of the system, or even the worst, which gave hope to people of Delhi.

In April 2025, another incident occurred, which drew nationwide attention when farmer Gajendra Singh died by suicide during an AAP rally in Delhi. And the most shocking part was the continuation of the political rally even as the incident unfolded, attracting widespread criticism and raising concerns about leadership response and political sensitivity during a human tragedy.

Simultaneously, the government faced a major internal political crisis when founding members Yogendra Yadav and Prashant Bhushan were expelled from the party after questioning the leadership’s functioning. Both accused Kejriwal of running the party undemocratically. “AAP is now run by a Khaap (panchayat). “All dreams of a movement have been shattered by a small coterie and a dictator,” Prashant Bhushan said, which is how the party and government were completely ruled by a single man under the name of a democratic setup. It exposed the project’s internal instability and contradicted its image of transparent, principled governance.

Policy announcements and limited structural impact

During its first year, the Aam Aadmi Party government implemented a number of policy measures and initiatives billed as governance improvements. Among the most visible was the Odd-Even vehicle rationing programme, which was adopted in January 2016 as an experimental solution to combat Delhi’s chronic air pollution and traffic congestion. According to the detailed study analysing pollution data across multiple locations in Delhi, including Punjabi Bagh, RK Puram, Anand Vihar, Mandir Marg, NSIT Dwarka, and Shadipur, the scheme had an inconsistent and limited impact on overall pollution levels.

Importantly, the most harmful pollutants, PM2.5 and PM10, remained significantly above both national and World Health Organisation safety limits during the Odd-Even period. In several areas, including NSIT Dwarka and Mandir Marg, pollution levels either showed negligible improvement or increased during the implementation period. The study concluded that vehicular restrictions alone could not substantially reduce pollution, as major contributing factors such as construction dust, industrial emissions, waste burning, and cross-border pollution remained unaddressed.

In addition to the Odd-Even scheme, the government launched initiatives such as an anti-corruption helpline, approval of e-rickshaw licences, regularisation of unauthorised colonies, and restrictions on slum demolitions. While these measures were presented as governance reforms, their structural impact during the initial year remained limited. The approach adopted by the AAP government was short-term interventions rather than structural reforms. Their aim was never to sustainably grow the country’s capital, but rather to provide a short-term solution for themselves as heroic figures before the Delhi people.

BJP Government’s first year: Governance and structural initiatives

Recently, the BJP government completed its first year in office in Delhi. Its governance approach reflected a shift towards administrative execution, infrastructure development, and structural civic management. Unlike the previous government, which focused on subsidies and announcement-driven measures. The first year of the BJP government was focused on the longstanding issues such as waste management, urban infrastructure, pollution control and institutional coordination. In the initial phase, the government’s efforts focused on improving infrastructure, strengthening civic services, and implementing rules to support long-term urban management.

Yamuna cleaning and sewage infrastructure changes

The BJP government started a structured plan to address sewage discharges and river pollution. It focuses on long-term infrastructure solutions. The government launched plans to connect 20 major drains to sewage treatment plants (STPs), which will help prevent untreated sewage from entering the Yamuna. New STPs are constructed while existing plants are being upgraded to improve the treatment capacity and compliance. Additionally, the government has launched a large-scale sewer connectivity programme. Under the programme, 13000 sewer connections in slum areas and approximately 2.5 lakh connections in residential colonies are targeted for untreated domestic sewage discharge. River rejuvenation operations include clearing encroachments and restoring almost 1,600 hectares of the Yamuna floodplain through plantation and ecological restoration projects. A dedicated special task force has been established, with a clear deadline to achieve quantifiable progress in river cleaning through structural interventions.

Public transport expansion and electric bus infrastructure

The BJP government has promoted the growth and expansion of Delhi’s public transport fleet. Primarily, it focused on electric buses to reduce pollution and improve operational efficiency. Over 500 new buses have been added, bringing the total number of electric buses to more than 4,000. Now, Delhi has one of the largest electric bus networks. The government aims to increase these numbers to 7500 buses by 2026 and 14000 electric buses by 2028. New interstate electric bus lines, such as the Delhi-Panipat corridor, have been introduced to promote regional connectivity. The expansion is part of a larger effort to update public transportation infrastructure, reduce vehicle emissions, and increase accessibility.

Healthcare infrastructure expansion through Ayushman Arogya Mandirs

The BJP government has built 319 Ayushman Arogya Mandirs across Delhi to improve primary healthcare infrastructure, with a long-term goal of establishing 1,100 centres serving every Assembly constituency. Outpatient care, diagnostic testing, medication distribution, immunisation, maternal healthcare, and preventive services are all included in the comprehensive healthcare services offered by these centres.

These centres are built as permanent infrastructure connected to national healthcare systems such as Ayushman Bharat and digital health records, in contrast to temporary or portable healthcare facilities. Through the expansion of institutional infrastructure, the emphasis has been on enhancing healthcare coverage, service quality, and accessibility.

Landfill clearance acceleration and Waste Management

The government has increased landfill remediation efforts by appointing additional biomining agencies and increasing waste processing capacity from approximately 15,000 tonnes per day to 25,000 tonnes per day. At the Okhla landfill site, over 56 lakh metric tonnes of legacy waste have been processed, reducing landfill height significantly and reclaiming more than 30 acres of land. Fresh garbage dumping at certain landfill sites has been stopped to enable permanent remediation. Phase-II and Phase-III biomining operations have been launched, supported by dedicated funding and infrastructure expansion. The government has set a long-term target to eliminate landfill sites by 2028.

Power infrastructure modernisation and underground cabling

The BJP government has initiated large-scale underground cabling projects to modernise Delhi’s electricity infrastructure and improve safety. A pilot underground cabling project has been launched in Shalimar Bagh, replacing overhead wires with underground networks. The government has allocated ₹100 crore for the phased expansion of underground cabling and approved a ₹463 crore project covering 125 colonies.

Long-term infrastructure modernisation plans worth approximately ₹17,000 crore include underground cable expansion, grid strengthening, and installation of modern monitoring systems. The objective is to improve reliability, safety, and the quality of urban infrastructure by reducing reliance on overhead power distribution.

Direct comparison: Governance models and administrative outcomes

The governance approaches reveal fundamentally different administrative goals and governance models. The Aam Aadmi Party government’s first year was marked by subsidy-driven policies, political controversies, and institutional confrontation. While these actions provide immediate political visibility and short-term public relief, they do not address the structural challenges faced by Delhi’s people.

In contrast, the BJP government’s first year has focused on structural governance interventions, infrastructure expansion, and institutional execution. Initiatives such as sewer connectivity expansion, accelerated landfill remediation, underground power cabling, healthcare infrastructure development, and public transport modernisation reflect a governance approach centred on long-term capacity building rather than short-term policy announcements.

While subsidies primarily redistribute financial resources, infrastructure investments create long-term public assets that improve governance efficiency, environmental sustainability, and urban functionality. Structural measures such as waste-processing infrastructure, sewage-treatment expansion, and power-network modernisation directly address the root causes of urban governance challenges.

The contrast between the two governance approaches highlights the difference between consumption-driven governance and structural governance. The AAP governance got immediate political visibility, while the BJP governance focuses on long-term administrative capability and infrastructure development.

Conclusion: Governance beyond political narrative

The completion of one year of the BJP government in Delhi has triggered political debate and competing narratives. However, governance must ultimately be assessed not through political messaging but through administrative record and structural outcomes. The first year of the Aam Aadmi Party government in 2015–16 was marked by subsidy expansion, internal instability, institutional confrontation, and limited structural reform. In contrast, the BJP government’s first year reflects a governance approach focused on infrastructure development, institutional execution, and long-term urban management.

Urban governance requires sustained structural investment in infrastructure, environmental management, and public service delivery. While political narratives may shift with time, administrative outcomes remain measurable and consequential. The long-term impact of governance is determined not by announcements or short-term relief measures, but by the strength of institutions, infrastructure, and structural reforms implemented during a government’s tenure.

As Delhi continues to face complex urban challenges, governance effectiveness will ultimately be judged by the ability to deliver lasting structural improvements rather than temporary political visibility.