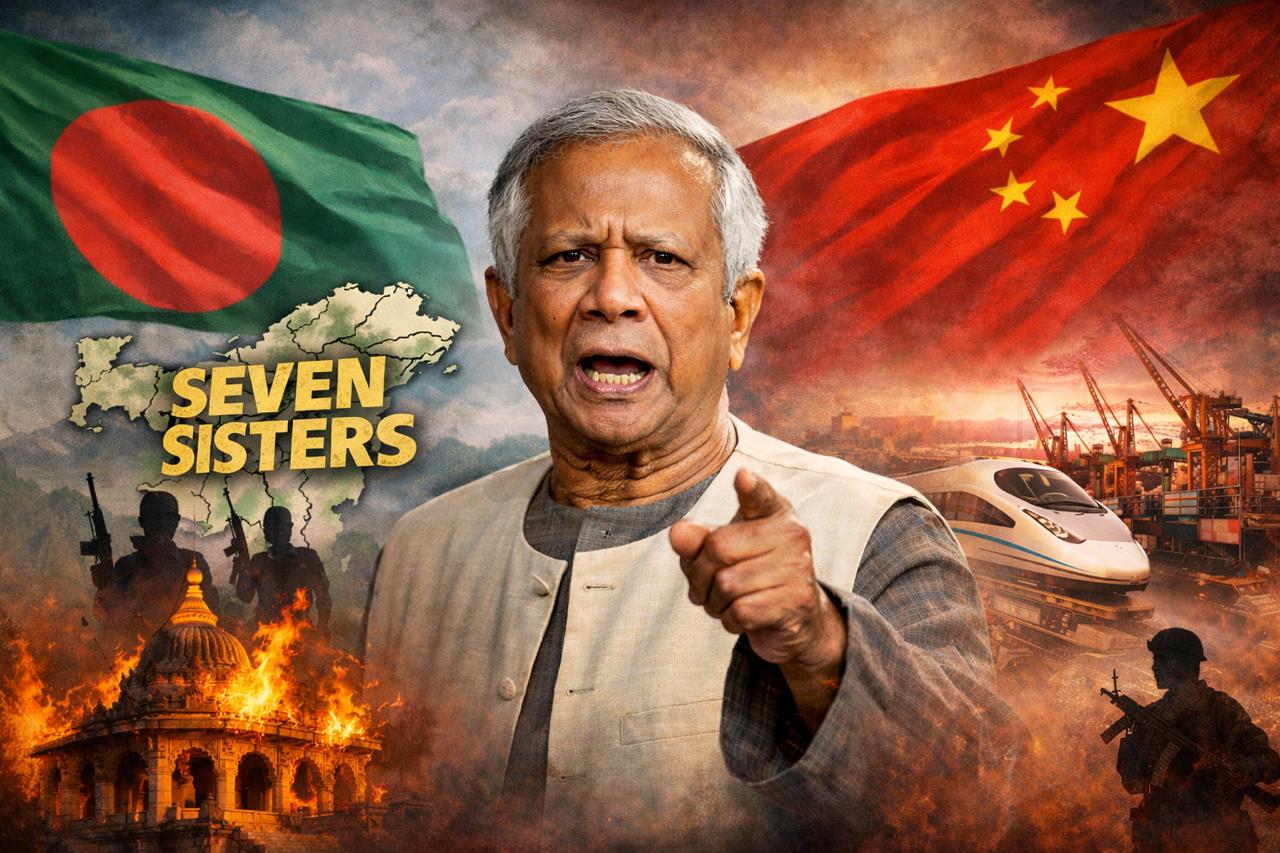

Muhammad Yunus and the ‘seven sisters’ dog whistle: How Bangladesh’s outgoing chief rekindled tensions with India and whitewashed attacks on Hindus

Muhammad Yunus did not step down quietly after the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) swept the elections. Instead of using his farewell address to heal wounds left by an unstable 18-month interim regime, Yunus chose to project defiance outward, most conspicuously at India with his reference to the ‘seven sisters‘ while carefully sidestepping uncomfortable questions about his own failures at home. Facing sustained criticism for failing to restore democratic normalcy and for presiding over a period marked by repeated attacks on Hindu minorities, Yunus used his final speech less as an exercise in accountability and more as a political counter-offensive wrapped in nationalist rhetoric. Nationalism for export, evasion at home Yunus headed the interim government in the aftermath of Sheikh Hasina’s ouster in August 2024, at a time when Bangladesh was already grappling with institutional decay, political uncertainty, and a serious breakdown in law and order. The post-uprising period saw targeted violence against Hindu minorities, temple vandalism, intimidation of minorities, and the emboldening of Islamist radical groups across several districts. Yet in his farewell address, Yunus offered no introspection. There was no acknowledgement of the fear among Hindu citizens, no admission of administrative lapses, and no recognition of the interim regime’s selective enforcement of law. Instead, he painted his tenure as a triumphant story of reform, boasting of restored “sovereignty, national interest, and dignity,” and declaring that Bangladesh was “no longer submissive or guided by others’ directives.” The subtext was obvious. This was not aimed at an abstract global audience. It was aimed squarely at New Delhi. The “Seven Sisters” dog whistle The political signalling became unmistakable when Yunus spoke of future economic integration involving Nepal, Bhutan, and the “Seven Sisters”, a term commonly used for India’s northeastern states, without once naming India. “Our open seas are not just borders; they are gateways to the global economy. With Nepal, Bhutan, and the Seven Sisters, this region has immense economic potential,” Yunus said, sketching a vision of Bangladesh as the hub of a new sub-regional economic space. This was not diplomatic clumsiness. It was semantic engineering with a purpose. By grouping India’s northeastern states, an integral, non-negotiable part of the Indian Union, alongside sovereign countries, Yunus blurred established political boundaries. The implication was subtle but loaded: the Northeast was being framed not as an internal part of India, but as a separate economic and geopolitical unit that could be reorganised around Bangladesh’s ports and maritime access. For New Delhi, this is not an academic concern. For years, India has invested heavily in connectivity and infrastructure through Bangladesh precisely to integrate the Northeast more firmly with the rest of the country. Yunus’s formulation tries to invert that narrative, implying that the region’s future access and opportunities would increasingly depend on Dhaka’s strategic choices rather than Indian planning. In a region with a long history of insurgency, external interference, and separatist propaganda, such language is not neutral. It functions as a dog whistle to old balkanisation narratives, whether Yunus admits it or not. The China card and “strategic balance” Yunus then doubled down by foregrounding “strategic balance” and highlighting deeper ties with China, as well as with Japan, the US, and Europe. He specifically cited progress on Chinese-backed projects such as the Teesta River initiative, located uncomfortably close to India’s strategically vital Siliguri corridor, and a major hospital project in Nilphamari. Rather than reassuring regional partners, Yunus seemed intent on signalling that Bangladesh would no longer prioritise Indian security sensitivities. The message was clear: Dhaka under his stewardship had options, and Beijing was a central one. This is a familiar script across South Asia. “Multi-alignment” and “strategic balance” often translate into inviting Chinese capital and influence into geopolitically sensitive spaces, using it as leverage against neighbouring countries. When paired with ambiguous rhetoric about India’s Northeast, the pattern becomes hard to ignore: dilute India’s centrality, normalise China’s presence, and dress it up as sovereign assertion. The military undertone Yunus’s reference to military modernisation and the need to strengthen Bangladesh’s armed forces to “counter any aggression” added another hard edge to his speech. The phrase was vague, but in the context of his broader sovereignty narrative and pointed regional references, it was clearly not accidental. For a departing interim head to inject such language into a farewell address is less about defence policy and more about strategic posturing. What Yunus didn’t say Perhaps

Muhammad Yunus did not step down quietly after the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) swept the elections. Instead of using his farewell address to heal wounds left by an unstable 18-month interim regime, Yunus chose to project defiance outward, most conspicuously at India with his reference to the ‘seven sisters‘ while carefully sidestepping uncomfortable questions about his own failures at home.

Facing sustained criticism for failing to restore democratic normalcy and for presiding over a period marked by repeated attacks on Hindu minorities, Yunus used his final speech less as an exercise in accountability and more as a political counter-offensive wrapped in nationalist rhetoric.

Nationalism for export, evasion at home

Yunus headed the interim government in the aftermath of Sheikh Hasina’s ouster in August 2024, at a time when Bangladesh was already grappling with institutional decay, political uncertainty, and a serious breakdown in law and order. The post-uprising period saw targeted violence against Hindu minorities, temple vandalism, intimidation of minorities, and the emboldening of Islamist radical groups across several districts.

Yet in his farewell address, Yunus offered no introspection. There was no acknowledgement of the fear among Hindu citizens, no admission of administrative lapses, and no recognition of the interim regime’s selective enforcement of law. Instead, he painted his tenure as a triumphant story of reform, boasting of restored “sovereignty, national interest, and dignity,” and declaring that Bangladesh was “no longer submissive or guided by others’ directives.”

The subtext was obvious. This was not aimed at an abstract global audience. It was aimed squarely at New Delhi.

The “Seven Sisters” dog whistle

The political signalling became unmistakable when Yunus spoke of future economic integration involving Nepal, Bhutan, and the “Seven Sisters”, a term commonly used for India’s northeastern states, without once naming India.

“Our open seas are not just borders; they are gateways to the global economy. With Nepal, Bhutan, and the Seven Sisters, this region has immense economic potential,” Yunus said, sketching a vision of Bangladesh as the hub of a new sub-regional economic space.

This was not diplomatic clumsiness. It was semantic engineering with a purpose.

By grouping India’s northeastern states, an integral, non-negotiable part of the Indian Union, alongside sovereign countries, Yunus blurred established political boundaries. The implication was subtle but loaded: the Northeast was being framed not as an internal part of India, but as a separate economic and geopolitical unit that could be reorganised around Bangladesh’s ports and maritime access.

For New Delhi, this is not an academic concern. For years, India has invested heavily in connectivity and infrastructure through Bangladesh precisely to integrate the Northeast more firmly with the rest of the country. Yunus’s formulation tries to invert that narrative, implying that the region’s future access and opportunities would increasingly depend on Dhaka’s strategic choices rather than Indian planning.

In a region with a long history of insurgency, external interference, and separatist propaganda, such language is not neutral. It functions as a dog whistle to old balkanisation narratives, whether Yunus admits it or not.

The China card and “strategic balance”

Yunus then doubled down by foregrounding “strategic balance” and highlighting deeper ties with China, as well as with Japan, the US, and Europe. He specifically cited progress on Chinese-backed projects such as the Teesta River initiative, located uncomfortably close to India’s strategically vital Siliguri corridor, and a major hospital project in Nilphamari.

Rather than reassuring regional partners, Yunus seemed intent on signalling that Bangladesh would no longer prioritise Indian security sensitivities. The message was clear: Dhaka under his stewardship had options, and Beijing was a central one.

This is a familiar script across South Asia. “Multi-alignment” and “strategic balance” often translate into inviting Chinese capital and influence into geopolitically sensitive spaces, using it as leverage against neighbouring countries. When paired with ambiguous rhetoric about India’s Northeast, the pattern becomes hard to ignore: dilute India’s centrality, normalise China’s presence, and dress it up as sovereign assertion.

The military undertone

Yunus’s reference to military modernisation and the need to strengthen Bangladesh’s armed forces to “counter any aggression” added another hard edge to his speech. The phrase was vague, but in the context of his broader sovereignty narrative and pointed regional references, it was clearly not accidental.

For a departing interim head to inject such language into a farewell address is less about defence policy and more about strategic posturing.

What Yunus didn’t say

Perhaps the most telling aspect of the speech was what it omitted.

There was no reckoning with the interim government’s failure to reassure minorities. No acknowledgement of the repeated attacks on Hindus. No admission that the state response was often slow, selective, or politically constrained. No reflection on the core promise of the interim setup: to restore democratic confidence and basic security for all citizens.

Instead, Yunus chose to shift the spotlight outward, toward grand regional visions, foreign policy bravado, and carefully curated defiance of India. In one instance, Yunus even downplayed the systematic targeting of Hindus in Bangladesh, stating that those incidents were criminal in nature and not communal. By defending such incidents, Yunus was sending a message to the rioters: come what may, he will continue to shield them, and attacks on Hindus can go unabated.

A parting shot, not a statesman’s exit

Having resigned after the BNP’s electoral victory, Yunus could have used his final address to lower temperatures and ease the path for a diplomatic reset between Dhaka and New Delhi. Instead, he chose to leave behind a narrative landmine, one that reframes India’s Northeast, elevates China’s role, and entrenches suspicion in bilateral ties.

Yunus’ farewell reads less like a unifying closing chapter and more like a defensive political statement shaped by domestic pressure and criticism. By dodging accountability at home and flirting with geopolitical provocation abroad, Muhammad Yunus exits office, leaving behind not clarity, but unanswered questions, about democracy, minority protection, and the wisdom of playing semantic and strategic games in a region where history shows that words can have very real consequences.

Because no amount of rhetorical “sovereignty” or “strategic balance” can change a basic fact: India’s Northeast is India, and treating it otherwise is not diplomacy, it is destabilising posturing. And it will have deep geopolitical repercussions, something which Yunus possibly wants the incoming BNP to face after Bangladesh’s populace rejected his tumultuous regime.